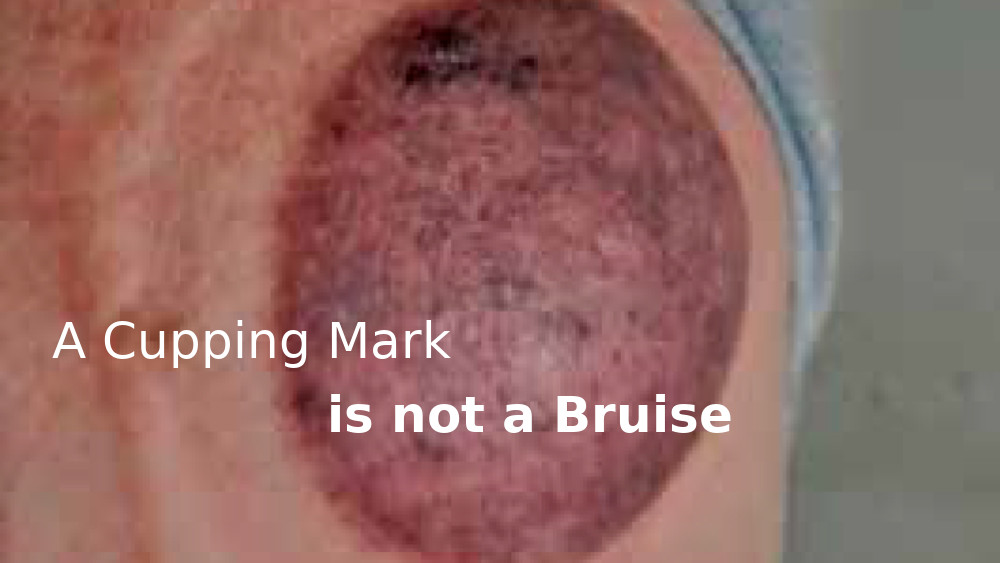

This essay offers some practical insights into cupping marks and explains why they should not be interpreted as bruises.

THERE IS NO procedure performed in current medical practice, or in any other activity in our present-day culture, that familiarises us with the idea that the marks that can be produced by cupping are the outcome of a positive and beneficial therapeutic process. It is understandable therefore that they can be both perplexing and confronting, and it is not hard to imagine patients asking themselves, “How can these marks be consistent with a therapeutic procedure?”

The time has arrived to clear up any uncertainties and highlight the positives because, apart from some brief accounts, I believe the topic has never been written about before, and unfortunately there is a common notion that cupping marks are bruises; hence they are often mistakenly referred to a “cupping bruises”. The term “discolouration” should also be avoided as it gives the impression of being either undesirable or some form of skin pathology.

The no-fuss term “cupping mark” should be adopted because among the people of diverse cultures who have traditionally practised cupping, a technical or “official” title has never been given for them. They are quite simply a matter of routine in the course of treatment. While the Chinese call them yinzi, meaning “marks,” the Greeks in northwestern Thessaly for example use the term dachylidia indicating “rings”. In the words of Mrs Fontini Stravou from the mountainous village of Koniska in central Greece: “A bruise is due to an injury to the body. The cupping mark is a different thing. In Greece we don’t regard cupping marks as bruises. And Mrs Maria Petariki, who was born and lives in Hania, Crete, explained: “The more coldness and pain, the darker (blue and purple) the marks are. They are a good thing”.

Those who grow up with cupping know that the mark is a meaningful and encouraging indication that some variety of pathogen(s) has been brought to the surface by the drawing power of the cupping vessel. It is a visible sign of success, and is in no way “unnatural” or at odds with any stage of the healing process. As a point of emphasis, it should be understood that this does not mean that cupping without producing marks has been unsuccessful. Some of the instances where marks are not brought about include performing a light form of Russian cupping massage for relaxation, restoring vitality and spirit after illness or emotional distress with soft cupping to achieve a similar effect to light massage done with tender loving care to recuperate the body and soul, and the powerful effect of applying a cup with the softest and most delicate touch down on the skin imaginable to restore strength and integrity to chronic tissue weakness (Bentley, 2011).

Thinking of cupping marks as bruises may also conjure up the notion that they must be the result of a painful procedure. On the contrary, cupping performed correctly, with the appropriate choice of method and the correct level of suction to suit the patient’s strength and condition, is always a comfortable and satisfying experience.

Furthermore, an even more problematic issue arises when cupping (and gua sha) (1) marks are misinterpreted as signs of abuse (Asnes and Wisotsky 1981, Eagle, Manber and Kanzler 1996, Davis 2000, Morris 2000 et al). Only a little over 10 years ago I was nominated by Vietnamese community leaders in Melbourne to head a 12-month research project funded by the Department of Human Services (Victoria) titled Folk Medical Practices in the Vietnamese Community. A pressing concern for the community was to see an end to this serious error of judgment. One of the documents produced was sent to all doctors and teachers throughout Victoria explaining the rationale and meaning of the marks according to culturally informed practice, and how to distinguish them from bruises and inflicted maltreatment.

Indications of proof

To date there has been no published research on the “substance” of the cupping mark, nor to my knowledge are there any trials under way. Nevertheless, it could be argued that cupping marks actually fulfill a number of essential scientific prerequisites. Their characteristics are repeatedly displayed as a catalogue of diagnostic indicators consistent with a well-developed classificatory index of observed and sensory-based criterion, that have been tested and accepted by all the world’s scholarly medical systems, except biomedicine, as well as by all the folk medical traditions since antiquity.

Given cupping’s longevity and the trust that many people have in its efficacy, it is a living heritage that is rare in this everchanging world. I hope that in the near future we will see a shift in our medical way of thinking to a more flexible model able to accommodate different paths of healing and alternative systems of patient response analysis, rather than being geared to objective and reductionist standards.

In addition, it is worth bearing in mind that if not for its long cross-cultural career, in all probability we would not even have the practice of cupping today, since from the very beginning of the biomedical era around the 1880s, the newly emerging fraternity did all it could to discredit traditional practices including cupping and their explanations concerning how we get sick and how best to deal with pain and illness. Distilled simply, in order to secure exclusive legitimacy for its practitioners and attain medical dominance, as well as provide a platform for pharmaceutical companies to prosper, Western medicine required a total separation from the past. Ironically, only 50 years earlier, Thomas Wakely, the editor of the Lancet (the celebrated British journal of medicine) wrote the preface to Samuel Bayfield’s book The Art of Cupping (1823) urging medical students to explore its contents because “those who are conversant with the subject will be amply repaid…” (2)

The only kind of techno-science based information to relate is what I was told during three days spent observing therapists performing stationary and sliding cupping at the Australian Institute for Sport (AIS) some 20 years ago.

“Blood without movement is no longer functioning as ‘blood’ and becomes a stagnant agency detrimental to health.”

The head massage therapist at the time, Barry Cooper, said one athlete was cupped and a round black mark produced. Immediately a tissue sample was whisked off to a nearby laboratory for microscopic examination to determine the composition of the dark pigmentation. The finding was “old blood”. It can be presumed this was bound in a muscle and drawn to the surface, just as a pool of blood resulting from a corked thigh can occupy the tissue spaces within a muscle belly and be liberated to the surface by cupping. It follows as logical that the longer that blood is not moving, the more it thickens, congeals and darkens. Indeed blood without movement is no longer functioning as “blood” and becomes a stagnant agency detrimental to health. There is no better way of shifting blood stagnation than with cupping, and in such cases you can be guaranteed that a dark mark is going to be produced. There is also every chance that following treatment the person’s pain will be greatly relieved.

Stefan Becker, a Brisbane based chiropractor, adds another plausible dimension to the discussion: “If the muscles are chronically tight in an area, the muscle contraction could restrict blood vessels, slowing down blood flow which could thicken the blood through platelet activity. Cupping could draw stagnant blood and toxins through the muscle to restore blood flow in these areas of chronic myospasm. The act of cupping would also bring phagocytic activity to the area thus ‘cleaning it up’.”

Coincidentally, the AIS laboratory “old blood” finding strikes a chord with traditional interpretations concerning dark cupping marks, and confirms that old or bad blood has been dormant within the body for a long time. The finding of “old blood” also lends credibility to those scholarly and folk medical systems that often refer to pain being caused by “bad blood”. Critics with vested interests, and with little or no experience of the subject matter, typically speak of this concept in disparaging terms.

In this light, it is limiting and ill-informed in every sense to regard the marks as some sort of undesirable outcome to be avoided at all costs. It should be worthy to know as well that once a patient is in the know, they often even become proud of their marks – and for good reason, as we will now discover. The stages of a cupping treatment

According to every cupping tradition, the marks are always the result of certain pathological agents being released from deep within the body, or from the superficial level including the subcutaneous skin layers and the fascia. Long experience concerning the mechanism of cupping and the appearance of cupping marks can be summarised as follows:

Cause: Injury, tension and climatic effects such as coldness (often felt deep within chronic injury), wind (including drafts and air-conditioning causing head and muscle aches) and heat (counting blow heaters that can cause dry hot throat and other febrile reactions) are among the most important precursors why we suffer illness and pain.

Method: Cupping is an efficient and rational means of withdrawing the infiltration and cumulative effects of these internal and external etiological factors.

Marks: Are the physical outcome of pathogens, toxins, blockages and impurities (waste products) that are an undesirable presence in the body.

Result: Having been freed from inside and drawn to the skin surface, a pathogenic influence causing a cupping mark is resolved in two ways. Some of it passes directly from the body into the atmosphere, and a certain amount is resolved by innate dispersing processes that function at the superficial level, including the local blood supply and lymphatic activity. Pertaining to cupping and its influence on the fascia and the ground substance (Bentley, 2013) means it is also likely to promote an additional immunological boost to what Paoletti (2006:158) describes as “the first defensive barrier”.

Mapping locations of pain & illness

In 1998, a chemist in Ioannina, northwestern Greece, by the name of Dr Zarharhin described cupping “as a very good practical technique”. He added, “People who do it look at the picture of the back”, meaning that the indications of pain and illness are delivered to the surface and there to be observed. The significance of the marks is highlighted in the following case.

In Ioannina I observed a group of men gathered around a man who was performing traditional (glass and flame) cupping on his friend who had developed the flu earlier that morning.

The protocol he used went like this. Five glass-cupping vessels were rapidly applied to one area of the upper back. Immediately following the application of the fifth cup, the first cup was taken off and reapplied to a new site. So too the second cup, then the third, fourth and fifth. This procedure went on until the five cups had each been reapplied bilaterally throughout the entire back from the upper margins of the trapezius muscles down to around T10 and including the sides. This entire process was then repeated another four times (3).

When completed, the oldest man, who appeared ancient, arose slowly from his chair, shuffled around the table and pointed his spindly index finger at each of the four locations where a very dark cupping mark had appeared. Each time he did this he fixed me with a stern gaze and growled with satisfaction—to the merriment of the others —until finally his mouth transformed into a knowing smile as he curled back his finger and made a thumbs-up gesture. The blatant hue of each mark identified where the major concentrations of the offending cold pathogens were located. The man who performed the cupping then resumed with part two of the treatment. He reapplied a cup on each of the four-standout marks for two to three minutes to withdraw any residual pathogenic coldness from deeper levels of the body. In this case, it is important that the strong stationary cup is left active for no more than a few minutes, otherwise its action becomes reducing and sedating— which would be called for when treating tight hard muscles but is not appropriate when the focus is to draw out pathogenic influences without reducing the strength of the body. Due to his acute condition, the men suggested that he get treated one time per day for three days in a row.

Marks as diagnostic fact finders

The list below identifies an array of cupping mark presentations as they occur immediately after a cupping vessel has been removed from the skin, as well as a brief diagnostic synopsis of each. This differential analysis is based on traditional Chinese medical thinking, which offers the most comprehensive and methodical reckoning available on this subject.

In folk systems such as Greek, Lithuanian and Vietnamese practice nowadays, the evaluation of cupping marks does not pick up on the same degrees of variation or subtlety.

- Cupping marks that display a fresh red colour indicate a recent traumatic injury with accompanying heat.

- Black, deep purple or deep blue indicates blood stagnation (Pic 1). It occurs when an injury or illness (including strong coldness inducing blood stasis) has resided in the body for a long time. A robust exogenous pathogenic agent such as the combination of wind with cold can also quickly manifest as a dark mark. It is telling that many massage therapists who receive cupping for the first time to the margins between the three deltoid heads frequently display dark marks. This indicates that the shoulder girdle has become congested due to over-use. It is recommended that MTs get cupping to these spaces on a monthly basis to keep the region in good order.

- A light pink or pale blue mark indicates mild coldness. (See the essay “Cupping Deficiency” (4) )

- A pale or white mark that fades quickly indicates a lack of energy and function (qi).

- A mottled presentation comprising crimson (or red) and white or lighter elements represents the condition where deficient body energy (whiteness) impedes the blood circulation (redness). (Pic 2.)

- Red dotting indicates the presence of a heat toxin due to blockage causing pent-up heat, which the Chinese call sha (Bentley, 2011). These small bright-red dots also commonly result from sliding cupping, which due to its constant state of motion tends to draw from more superficial levels compared to stationary cups, which draw from the full entitlement of depth possible. Even when slowly sliding silicone-cupping vessels to rectify the fascia using the modern cupping technique, the innate mechanism of drawing outwards will sometimes inevitably cause certain factors lying within the underlying tissue to emerge at the surface. Sha made apparent by cupping typically resolves in a short period of time. (Pic 3).

- A protrusion (an elevation above the regular surface level) of a tight black or purple knot of tissue indicates clotted dormant blood of fixed location that by degrees of form can even look similar to a varicose lump. It is a source of sharp stabbing long-term pain and immobility. No other method can draw this from the body like cupping. In Vietnamese practice, both the cause and the manifestation are called “poison wind”. Sometimes an elevated hard knot, which at its centre is white or paler than the surrounding tissue emerges and indicates cold phlegm. The vacuum effect of cupping can produce a soft and full-bodied swelling contained within the parameter of the cupping vessel. This will diminish quickly. It represents generalised oedema (dampness).

- In the absence of a cupping mark, sometimes droplets of clear fluid can be seen within the interior of a cup. On occasions also, a sticky dull yellow mucosal-type residue is observed towards the inner apex of a cup. Clear water type droplets indicate dampness escaping beyond the protective skin layer, while thicker residues indicate the discharge of phlegm caused by heat drying regular fluids.

- On rare occasions, a blister or blisters containing fluid may appear inside the perimeter of a stationary cup. This indicates the local area has superficial oedema (dampness). Caution needs to be taken to keep the area free from infection. The blisters should be carefully wiped with antiseptic, then covered with a sterile pad and left to reabsorb into the body. Regrettably, a cup applied too strongly and left on the body for more than 20 minutes may also cause blisters. Some practitioners who have performed the glass and flame method of applying a cup may be alarmed and think they have burned the area. This is not the case. An area that has received a burn will be red and painful.

Pic 1: A mottled cupping mark indicating insufficient strength (paleness) and sluggish circulation producing mild blood stasis (crimson/purple). When this evidence is noted, flash cupping performed by rapid on and off applications revives energy and moves the blood. It is a soothing and tonifying method that restores the integrity to soft tissue and removes dull or intermittent pain and feelings of weakness.

Pic 2: This very defined cupping mark is located above a medically diagnosed partially torn middle deltoid muscle injured nine months before this photo was taken. It identifies blood stagnation and features a proliferation of black, slightly elevated blood clots and swelling, reflecting deep, sharp persistent pain and immobility.

Pic 3: Small red dotting indicates the release of heat toxins (sha).

Temperature diagnostics

Another striking feature of certain pathogens emancipated and filtered up from inside to the surface is made apparent by certain definite thermal characteristics that accompany the release of a cupping vessel. When coldness is drawn from the body, as the lip of a cup is released the cupping therapist should be alert to the feeling of a draft of coldness escaping and contacting the fingers, like the brief initial blast of cold air felt when opening a freezer door. The skin where the cupping vessel was located will also feel cold. Conversely, when heat is drawn from the body, the therapist can place their open palm above the skin surface and feel the palpable warmth radiating from the treatment site, as is the case after using sliding cupping up and down the erector spinae muscles to treat women suffering hot flushes. The patient is most likely to also have a very definite awareness of heat literally “pouring out”, as it has been described many times in practice. This release provides great relief.

When to treat next?

Apart from some acute conditions such as the common cold or influenza, where daily treatment is advised for the first few days, the ongoing status of a cupping mark is frequently used to gauge when to repeat a treatment to the same location. It is vital to realise that while a cupping mark remains visible, the treatment is still active and in progress. Its presence is being maintained by the ongoing elimination of the pathogen.

In most cases even a strong coloured dark mark will be less fierce within 24 hours. Given a few more days it usually will be substantially reduced. In most cases, seven days will see it vanish. Sometimes, especially if a cup has been applied too strongly, a mark may last for 10 days or longer. Once a mark is close to resolution or has disappeared is an appropriate time to reapply a cup to the same site.

It is also consistent with healing to note that when the exact location of a former cupping session is cupped a second time, the show of a mark will be usually reduced by at least 40 per cent. Under certain circumstances, however, cupping marks can continue their form and reappear with little change. Even when receiving regular weekly treatment, smokers with toxins constantly being fed into the body consistently exhibit dark marks after being cupped anywhere in the thoracic region. So, too, do some athletes who carry out regular hard exercise without adequate stretching, fluid intake and relaxation.

Six reasons why a cupping mark is not a bruise

The list below is a brief summary of some of the critical differences between a cupping mark and a bruise.

- On many occasions cupping produces no marking, even when a robust volume of negative pressure (vacuum) is within the cup, because pathogens and other unwanted factors are not there to be drawn to the surface.

- By definition, a bruise occurs “as a result of a blow that does not break the skin” (Lackie, 2010), or otherwise, “bleeding in soft tissue resulting from a direct blow with a blunt instrument” (Kent, 2007). The lifting suction effect of a cupping vessel on the skin stands in stark contrast to the inward sinking dynamic of a blow to the surface. Furthermore, there is no trauma caused by the solid rim of a cup (see Pic 2).

- “A bruise changes colour, first to blue as a red pigment of haemoglobin loses its oxygen, and then to brown or yellow as the haemoglobin is broken down and reabsorbed”(Kent, 2007). This description of a bruise’s colour changes does not apply to the fading and resolution of a cupping mark. The fading of a cupping mark is a progressive lessening of the original hue without any different colour transitions.

- When we have a bruise, experience tells us that it is tender to touch (due to trauma). After cupping there is no such accompanying tenderness. Note: Only following over zealous and aggressive cupping can a bruise-associated yellow stain be produced, together with tenderness within and beyond the periphery of a cupping mark. Such a sign represents poor practice.

- Imagine a cup has been applied and produces a strong dark mark. After that has resolved and another cup is reapplied on the identical location, with the same suction level and for the same duration, the marking is typically only about half as ‘ferocious’ as the first time. By the third session, chances are the response will only be a faint showing. Usually by the fourth treatment no marking occurs. This is clearly a case of an internal pathogen or toxin being systematically resolved. This scenario would be the opposite if it were a bruise. The capillary damage incurred by a trauma to produce a bruise would increase with repeated assaults. The following is a further illustration. Picture two round cupping marks side by side, with a gap of 2-3 cm between each at the closest point. When they have faded to half their original form, apply a single cup over that gap with the same level of suction. Strong marking will be produced only in the previously un-cupped space between them. The hue formed in the margins of the former cups will a considerably lesser shade. This clearly indicates that the pathogen has been resolved to a significant extent within the range of the first two cups, compared to the “in-between” tissue that was unaffected by the first application.

- A bruise can be successfully cleared using cupping. Healing a large bruise for example, can be accelerated by applying a soft to moderate strength cup to the centre of the bruise and sliding it outwards beyond the bruise’s perimeter. Complete the treatment by repeating the above along successive margins as if following the spokes of an imaginary wheel. A bruise is after all a form of blood stagnation and cupping is excellent at dispersing blood stagnation.

Gaining informed consent

A challenge for practitioners is explaining how cupping works and the possibility that marks may appear. An explanation is best when it is easy to comprehend and does not labour the point. Here is a suggestion:

“I think it would be beneficial to do some cupping for you. It’s an ancient method for relieving sore muscles by promoting blood flow and stimulating the release of toxins. It is relaxing and comfortable, however it may bring some of those toxins to the surface, which will cause temporary marking [it’s an excellent idea to have some photos of marks to show]. They will fade within 24 hours and usually disappear within three to four days, though in some cases they may linger for a week or two.”

After checking for any contraindications and inquiring whether markings could cause any concern, you can then ask: “Are you fine to proceed?”

Endnotes

- (1) Compared to cupping marks, the markings produced by gua sha can be even more dramatic, less stylized and more difficult to decipher to the untrained eye.

- (2) Bayfield (1823) mostly gives instruction about wet cupping, with a short section devoted to dry cupping. Wet cupping is when the skin is superficially incised before a cupping vessel is placed over the incision in order to accentuate the release of blood. It is the safest and least invasive of all the bloodletting methods. Dry cupping is the historical term often used for regular cupping performed on an intact skin surface.

- (3) The practitioner’s manner of applying each cup was also calculated. Rather than alighting each cup on the skin in the usual way, he held each cup and with a loose downward flick of the wrist literally slapped each one onto the skin. The cup then instantaneously seizes the tissue and strongly pulls the pathogen to the surface. Additionally, this drawing dynamic is further enhanced as the cups become heated and expand the skin pores and open a conduit for the body to release unwanted and unhealthy factors.

- (4) The essay “Cupping Deficiency” highlights to use of the glass and flame cupping method to remove deep coldness associated with chronic injury and repair flaccid and unhealthy soft-tissue structure.

- (5) Besides visual and temperature indicators another intriguing phenomenon occurs when sheaths of superficial fascia are tight and a clicking sound, or a series of clicks, can be heard as a sliding cup moves over the skin. This we can presume is the sound of pockets of pent-up energy being released. On every occasion I have heard this, and in accounts from other practitioners, this audible feedback reflects a successful release of tension.

Bibliography

- Asnes, R.S. and Wisotsky D.H. (1981) Cupping lesions simulating child abuse. Journal of Pediatrics, Volume 99, Number 2, The C.V. Mosby Co. The United States of America.

- Bayfield, Samuel (1823) A Treatise on Practical Cupping. Joseph Butler. London.

- Bentley, Bruce (2010) Gua Sha: Smoothly scraping out the Sha. The Lantern 4 (2), 4 -9. Online. Available: www. healthtraditions.com.au

- Bentley, Bruce (2011) Cupping Deficiency. The Lantern 8 (2), 15–27. Online. Available: www.healthtraditions.com.au

- Bentley, Bruce (2013) Mending the Fascia with Modern Cupping. The Lantern 10 (3), 4-21. Online. Available: www. healthtraditions.com.au

- Bentley, Bruce (2014) Cupping’s Folk Medical Heritage: people in practice. In Cupping Therapy (3rd Ed) by Ilkay Chirali. Churchill Livingstone. China.

- Davis, Ruth E. (2000), Cultural Health Care or Child Abuse? The Southeast Asian Practice of Cao Gio. Journal of the Academy of Nurse Practitioners. Volume 12, Issue: 3, 89-95.

- Eagle, Kim, Manber, Helen and Kanzler, Mathew (1996) Images in clinical medicine: Consequences of cupping. The New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 335, Number 17.

- Kent, Michael (2006) The Oxford Dictionary of Sport, Science & Medicine. (3 Ed.) Oxford University Press. Published Online: Oxford Reference 2007. Accessed 1/2/2015.

- Lackie, John (2010) A Dictionary of Biomedicine. Oxford University Press. Published Online: Oxford Reference 2010. Accessed 1/2/2015.

Bruce Bentley studied Chinese medicine in Taiwan from 1976 until 1981. He has a Masters Degree in Health Studies based on his thesis entitled Cupping as Therapeutic Technology. He has investigated the Eastern tradition of cupping in Vietnam, and studied at the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Tibetan Medicine Hospital in Lhasa, Tibet, and at the Uighur Traditional Medicine Hospital in Urumqi, Xinjiang Provence, China. To research the Western practice of cupping, Bruce visited the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra where masseurs employ cupping to treat injuries and enhance performance, and in 1998 he went to Europe and North Africa, doing archival research on cupping at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London, and the Department for the History of Medicine at Rome University, followed by field-work in Sicily, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey, Morocco and Tunisia learning local cupping traditions. Bruce’s most recent research trip investigating cupping was in Cambodia during July 2003. He is also a state registered acupuncturist and Chinese herbalist and director of Health Traditions: www.healthtraditions.com.au.

First published in the Journal of the Australian Association of Massage Therapists, Winter 2015.

Top ↑