Cupping is commonly regarded as a reducing method to disperse stagnation and eliminate external pathogenic attack. However, cupping can be so much more, and is equally adept at remedying deficiency.

From discussions I have had, many practitioners are concerned and seeking information about cupping. One of the subjects of particular interest concerns the prospect of cupping for deficiency. Some claim it is impossible, because “cupping is a reducing method” while others have expressed confusion about the state of play. My immediate response is, “yes, it is certainly possible, but it must be performed correctly.”

The key to cupping deficiency – tonifying with cups – rests in gently placing a cup to the skin surface, and so bringing about a soft concentration of vacuum to a point or area of weakness and instability. Performed this way, cupping has the effect of drawing and nurturing qi and blood, and so becomes a method of tonification. Let’s first take an overview of cupping and help put this uncertainty to rest.

Tonification and sedation with cupping

Cupping is the application of vacuum to the skin surface for a therapeutic effect. However, in most of the available literature and within teaching circles, the status quo has cupping typically performed in a robust manner. Like other forms of therapy in Chinese medicine (CM), including acupuncture, tuina and gua sha, a strong method is a reducing method. The same holds true for cupping, and thus makes it suitable for conditions such as external pathogenic attack, release of tight muscles and soft tissue, and other conditions of excess (shi).

However, this is only one side of the yinyang and does not mean that cupping is intrinsically a sedating method. There are many applications for what I will hereafter call “tonification cupping”, including tonifying the Kidney yang with Shenshu (BL-23) points and treating all types of musculo-skeletal deficiency syndromes.

In the case of tonifying the Kidney yang, it so happens that many years ago I started seeing a spate of patients who, only a few days earlier, had consulted CM practitioners with lower back discomfort, tiredness and other symptoms clearly due to Kidney yang deficiency. They reported that after receiving cupping treatment to their lower back, they felt fatigued, colder than usual and emotionally drained. On examination, the cupping marks left from their treatments indicated strong cupping. This of course had no positive benefit – quite the reverse, in fact. The Kidney yang deficiency had been exacerbated by strong sedation. A poor result in anyone’s book!

This, by the way, was one of the hallmark reasons why I decided to begin teaching cupping. Here was such a good treatment method that clearly needed work. If the points Shenshu and the surrounding area had been warmed and cups had been placed softly, then these people would have felt much better.

According to my experience where tonification is required, the softer a cup is placed on the skin surface, the more profound and beneficial the healing experience. Tonifying Shenshu this way has had such a deep effect that, on occasion, some patients have been overjoyed and in tears. One patient said she was able to relax so deeply that she found the answer to an emotional difficulty that had haunted her for years, while another patient even described her treatment as “a religious experience”. All others have felt relaxed and comfortable with good improvement of symptoms, including feeling warm throughout the lower back. The Kidney pulse in turn always shows more strength and volume.

Long-term trauma also benefits from tonification cupping where there are clear signs of deficiency. I will deal further on with a case involving chronic shoulder injury, not only because is it a common clinical presentation, but also because following treatment, a positive and palpable change for the better can be readily detected.

So unlike improvements with some conditions, which can be obscure to discern without subjective feedback from the patient, or take a long time to respond, my experience is that immediate benefits can be felt and observed with soft tissue cupping rehabilitation.

I will now review the conditions that typically differentiate pain syndromes. Being related to musculo-skeletal injury, I will present the differences between acute and chronic injury as consistent with both a biomedical perspective and a Chinese medicine vantage point,which makes good sense by using language that rings true for patients.

Acute and chronic injury patterns

During the first stage of soft tissue damage caused by trauma, our body naturally responds by activating a series of acute reactions. Such a presentation is characterised by the distinguishing signs of sharp pain, pronounced heat (inflammation), redness, elevation (including swelling) and stiffness – all symptomatic of hyper-reactive processes brought into play by the body extending its capabilities to heal itself. This process (the acute stage) can proceed for a few days, weeks or even months, depending on the severity of the trauma, its location in the body, whether it might be a reinjured site, as well as how effective the treatment (if any) has been.

From a CM perspective, all the above is also predictable and occurs with the mobilisation of the yang to the external structures. In CM we can get good results at this stage with a number of different approaches, not least the use of acupuncture, whereby those dynamic thin slivers of therapy can enter deep into the injured structures without further triggering the acute phase, as can be the case with local administration of tuina or cupping. The other beneficial local treatment is the application of Chinese herbal liniments, soaks or plasters, which penetrate and assist in the task of repair.

“It is my assertion, having performed the tonification cupping treatment on many patients, that what had previously fallen away can be re-established and remodelled into normal healthy tissue.”

Unlike the standard biomedical response with ice, which does indeed relieve inflammation but unfortunately also reduces circulation and the healing process, the beauty of a well-constructed herbal injury formula is in a combination of herbs that cool and clear heat, while other herbs promote qi and blood, dissipate swelling and disperse bruising, and mend injured tissue. The further advantage of such an approach is the greatly reduced risk of recurrent weakness or rheumatism.

If not resolved by itself or successfully treated, after this acute time frame has elapsed, another set of conditions exert their influence on the injured soft tissue. It enters into a chronic phase, which can continue for an extended time, perhaps a lifetime. Chronic syndromes are characterised by the opposite of the acute mechanism. Because of the body’s extra effort in the acute stage to orchestrate healing, those elevated levels of activity falter and in time wear themselves out, and the reverse begins to take effect. Instead of a hyper-reactive response, the distinct opposite, a hypo-functional state, develops. This is the dynamic of exhausted yang collapsing into yin.

The typical characteristics of chronic or long-term injury are deep and constant aching pain, coldness – which can become more pronounced with age and injury duration and exacerbated by cold climate and environs, as well as the use of ice as so-called “rehabilitation” during the acute phase – depression (as opposed to elevation), where weakening of the tissue structure has given rise to the injury site being lower than the regular level of the body surface, and soft, flaccid, and irregular tissue structure, including adhesions.

This last point needs remembering because it is a valuable diagnostic focus and an opportunity par excellence via palpation to compare before and after treatment to feel for changes that have taken place. In addition, there is the opportunity to visually note whether what was previously sunken tissue has been elevated to the regular body surface level.

It is my assertion, having performed the tonification cupping treatment on many patients, that what had previously fallen away can be re-established and remodelled into normal healthy tissue, which serves as a valid indicator of treatment success.

The Chinese tonification cupping tradition

My first instruction in how to perform tonifying cups was from a man who lived near my house in the hills on the outskirts of Taipei, Taiwan, in 1976. He was not a doctor of CM, but a Daoist with a keen interest in health. One of the interesting practices he did at dawn each morning was to rub his hands over the leaves of plants to collect the pure yang of dew, and then gently massage it over his face. For a man in his 60s he had a peerless complexion. Shortly after having told him of my first experience seeing cupping performed, he paid me a visit and taught me a very different form of cupping.

He first lit a stick of moxa and held it inside a glass cup. He then quickly applied the cup, because the limited amount of vacuum generated by the ember of a moxa stick barely had enough suction to grip to the skin surface. This he called juiguan, being “moxa-cupping”. He went on to call it a form of buguan, the literal translation of the two characters being bu “to tonify” and guan meaning “cup”.

He told me he learned this method in his youth from one of his teachers in his provincial birthplace of Shandong. He recalled how cold the winters were and added that people knew how to combine cupping and moxibustion, to restore strength to deficient patterns of the Stomach, Spleen, Lungs and Kidneys. He also instructed that the smoke from the moxa herb Ai Ye (Artemisiae Argyi Folium), which swirls lightly inside the cup until it absorbs into the skin, is important for clearing coldness from the channels. As a sidenote, since then, when doing moxibustion, I often gently blow the smoke into a point I am heating, and believe it is an excellent practice to help move wind-colddamp, especially in cases of bi syndromes.

My Daoist friend also said to be sure to warm the rim of the cup, so it was comfortable and did not render a shock of chill to the body.

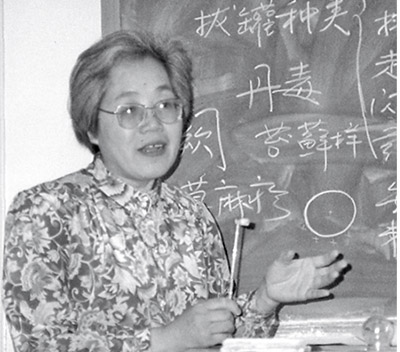

Dr Zhou in lecture mode at Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

On other occasions in Taiwan, I noted practitioners performing soft cupping for tonification, one of whom was my tuina teacher, the Buddhist monk Da Ti at the Guan Yin TCM Hospital. In 1996 I had the good fortune to be invited to the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, where a cupping course was presented for me.

Frequently my chief instructor, Dr Zhou Ling, used the term buguan to describe tonifying with cups, and while the tonifying method is addressed in some of the modern Chinese medical literature, there is little detail given beyond the requirement to apply the cups lightly for a short duration.

Again at the Traditional Tibetan Medical Hospital in Lhasa, Tibet, that same year, my chief instructor in cupping (Tibetan: sang porl), Dr Tse Wang Tan Pa, showed me the flame method of warming bronze cups because, as he said, “bronze warms better than glass, so it is preferable to treat cold problems during winter when there is deficiency”.

He followed by applying these heated bronze cups to a patient in a way that was much softer than the typical way cups were applied with strong suction in Tibet.

Tonification cups to counter cold

Cold is an externally contracted pathogen that very easily penetrates long-term injury, and will almost certainly do so if the opportunity arises. It is also likely to develop as an endogenous pathogen the longer an injury stays in the body, and the warm supporting nature of the yang diminishes as the injury sinks progressively deeper into the yin. Thus the demise of the yang happens especially at the deepest point of the injury, and it is from here that coldness will frequently meet with or drift upwards to contact the fingertips when penetrating and feeling deeply into an area of tissue collapse and deficiency.

Cold blockage, wind and dampness also frequently form an amalgamation of sorts and cause pathogenic patterns that move in with long-term injury. Importantly, all three are especially well removed by cupping.

For now I will concentrate on cold, because in my case study involving longterm shoulder injury, the presenting condition exhibits characteristics that are typical of the presence of cold and the way it affects the body. Cold is contractive so it sinks into the body and is coldest the deeper one is able to discover its presence. It is fixed in its location, it causes tight contracted sinews, is relieved by heat and made worse by cold, and it leads to decreased movement especially with tiredness (qi deficiency causing cold).

An assortment of cupping instruments used at the Tibetan Traditional Medical Hospital in Lhasa. Five bronze cupping vessels are shown at the top while resting on the tray are different sized yak horn cups with tubes attached to allow the air inside to be drawn out by the large clear pump at the foot of the picture. Also on the tray are two metal scarifiers used to nick the skin or vein for wet cupping.

My own experience, and that of colleague Michael Ellis, is that one of the strengths of Chinese medicine is its ability to rectify cold. Many of our most dramatic successes in practice have been when cold has been eliminated. Michael makes the point that an obvious priority for biomedicine is in applying anti-pyretic remedies; meaning it focuses on the submission of fever (using paracetemol), the elimination of infection (with antibiotics), and – more to the point in this context – reducing musculo-skeletal pain by applying ice externally while administering anti-inflammatory drugs internally. This seems to be based on the biomedical understanding of pain as being the result of “inflammation”. In contrast, biomedicine barely concedes the presence of cold as an illness aetiology or source of pain, nor the iatrogenic propensity of its own therapies to introduce a cold factor, or compound one already present in the body. Perhaps this is because, as Gunter Neeb noted during his seminar Unknotting Difficult Cases in Melbourne (June 2010), “fire can kill you quickly, whereas cold kills you slowly!” – to which I would add “and gets you in the end”!

“Cupping takes the cold, wind and damp from the texture of the skin, the muscle and the bone, but not from the organs. For this, it is best to use herbs.”

– Jamel Saadi Yakoub Tunisian herbalist

It is interesting to note that people in the East, while not forgetting the effect of cold, tend to be more aware of wind as deleterious to health, and blame it more readily as the cause of so many illnesses and aches and pains. In the European and Middle Eastern traditions of cupping, practitioners emphasise removing cold, although wind is also considered an important factor.

One of the most fascinating aspects of cupping is surely its practice all around the world, with all its variations of cultural identity, rationale and method. In all my research, one of the most inspiring people I had the good fortune to meet was Jamel Saadi Yakoub, a herbalist of the Tunisian tradition, who runs a dispensary in the medina of Tunis. He also speaks English very well. I spent most of a day, in April 1998, in his small shop ducking cascades of hanging herbs from the ceiling and every conceivable surface, enthralled by the conversation we had together with his older friend Mohamed Salah Amary by his side. They gave me their entire day, even to the point where poor Mohamed, with me in tow, spent at least a couple of hours trudging around on a blisteringly hot day just to find different locally made cupping vessels. Back at Jamal’s shop, one of the interesting things he said was, “Cupping takes the cold, wind and damp from the texture of the skin, the muscle and the bone, but not from the organs. For this, it is best to use herbs.”

Another person in Fez, Morocco, is Mrs Khadouj, who specialises in cupping, together with herbs, for helping women conceive. She said that the difficulty often lay with “coldness in the uterus” and used three cups applied next to each other above the pubic crest to draw coldness out. She recommended this practice be performed over three consecutive days. When the cups produced markings, she said there was a good chance of success, as the colouration was the cold from inside drawn to the skin surface. She also said, “after drawing out the cold, the body feels much, much warmer.”

The five levels of vacuum

Another cupper I admire for her knowledge and skill is Lina Volodina, a medical doctor from Russia and now an Australian resident. Back in the days of the Soviet Union, Lina specialised in paediatrics and used tiny pentop sized cups and a small vacuum pump when practising on her young patients. To bring some fun to those consultations, she began calling different levels of vacuum by different Russian animal names. A really strong cup she called a bear cup, one with slightly less strength she called a wolf; mild was a fox, and the soft was a rabbit cup. She decided on an appropriate level of vacuum to suit the signs and symptoms, just as we would as informed cuppers, using a compatible set of CM diagnostic indicators.

The five levels of vacuum. The soft level of vacuum to the left side of the photo produces a bu/tonifying effect while the stronger cups to the right have a xie/dispersing and reducing effect. Knowing how to adapt cupping to suit each patient is a mark of a first-class cupper.

After consideration of Lina’s four vacuum levels of cupping, I believe it is appropriate to establish a five-level platform of vacuum differences, as there needs to be a middle suction level, or median cup, in a way similar to the graded temperature scheme:

- being hot, warm, neutral, cool and cold

- used in diagnosis and treatment with Chinese herbal and dietary therapy.

I have christened these vacuum strengths from strong to soft according to Australian animals ranging from fierce to placid:

- crocodile (croc)

- Tasmanian devil

- possum

- bilby

- sugar glider.

The median (possum level) of vacuum is appropriate where a moderate degree of suction is enough to move a medium level of stagnation, or where a person’s sensitivity or emotional stamina is tested by stronger application.

Operation

When applying a cup, the strength of its grip to the skin surface is not determined by how long the flame has been left inside the cup, provided of course that the flame is still burning well and not petering out. Because negative pressure (vacuum) is based on the burn-out of oxygen, an ample flame will consume the oxygen in a small empty space in the blink of an eye. So there is no advantage in keeping the flame inside any longer than necessary – unless you are seeking to heat the inside of the cup – which is a different matter and will be discussed shortly. The degree of suction is essentially determined by the amount of time taken from the removal of the flame, till it touches down on the skin surface. To accomplish a strong “crocodile” cup, for example, the vessel must be shifted very quickly to the skin surface immediately following the removal of the flame. On the other hand, to apply a soft “sugar glider” cup, a couple of seconds should go by before a very soft touchdown. To do this “sugar glider” technique requires a gentle touch: the cupper’s mind is peaceful yet concentrated, the breath sinks to the dantian, the body demeanour is relaxed, even the cup has to be held with light fingertips surrounding its upper sphere to ensure a gentle landing – all qualities that occur simultaneously only when the yi (intention) is focused and compassionate.

I will now present a treatment procedure for a long-term shoulder injury. A similar procedure can be adopted for other musculo-skeletal conditions that have the same or similar presentations.

Case study: Long term shoulder injury

Alain is a 63-year-old massage therapist who suffers from a long-term injury to his shoulder and surrounding soft tissue. When he was seven years old, he strayed from his mother’s side and began to cross a busy road. Alarmed, his mother yanked his arm to pull him away from an oncoming vehicle. This caused a dislocation of his shoulder joint. He remembers the sharp pain and how his arm hung limp at his side as he was taken to a nearby hospital, where it was put back into position. Ever since, he has experienced fairly constant dull pain; “not too bad though” he says, “I’d rate it 2-3 out of 10 within the rhomboid major muscle and pectoralis major.” In addition, “I have decreased mobility, and stiffness which is getting worse as I get older, with the stiffness most noticeable within the glenohumeral joint, especially after a demanding week’s work”.

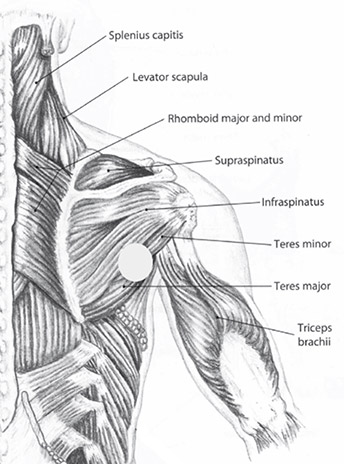

Muscles of the upper back (Biel, 2010: p.61): The area of deficiency is indicated as a white circle.

Examination of Alain’s shoulder region revealed the following. He had only partial range of movement with shoulder flexion (moving the arm forward from the side of the body), and with extension (taking the arm backwards directly in line from the side of the body), and discomfort and shortened range of movement when his arm was medially rotated (i.e. bending his arm and taking it towards his mid-back). All of these restrictions are consistent with injury sustained to the gleno-humeral joint with subsequent weakened strength and flexibility to the teres major, teres minor and infraspinatus: principal shoulder stabilising muscles that typically become problematic in response to injury.

But I was really interested in discovering if there was a place on Alain that showed signs of deficiency syndrome, whereupon I could apply tonification cupping. That proved to be located within a convergence of the three previously identified muscles (see diagram). Palpation and visual observation are the keys to determining the right place. Observation revealed that the area had sunken lower than the regular body level and from palpation it was noted that:

- The skin surface felt cool by comparison with the surrounding tissue.

- There was a distinct collapse of muscle tone.

- Sensitive penetration revealed errant tissue structure.

This location became my treatment focus. Briefly the rationale for this is: the deficiency site undermines all attempts by the surrounding muscles to be healthy and to function effectively, because each one acts as a synergistic lever for all the others. I will elaborate further on these palpatory findings during the treatment procedure.

As a CM practitioner not trained in the complexities of osteopathic examination procedures, I must confess I basically go with what I feel. I look for the location of the most significant deficiency signs and apply treatment accordingly. Further, Alain was a student of mine in class and I did not have the time to go into further examination. In the course of introducing the tonification cupping method, Alain volunteered for treatment and gave a brief description of his problem. Once all other class members had the opportunity to palpate the region and the location and feel of the deficiency, I proceeded with treatment.

Palpation method

Make contact with the skin surface and inspect throughout the region by gently palpating the area under examination with the finger pads. This region being checked should go beyond the original site of the injury to include a broad expanse of the surrounding surface geography. This is imperative because of the broad ranging ramifications of a complete shoulder injury, let alone, for example, a simpler yet still decidedly painful anterior deltoid tear or strain. Shoulder injury can trigger a far-reaching disruption to regional soft tissue integrity and manifest as different tissue irregularities, for example the inter-connected spread of the surface fascia (connective tissue) in itself suffers throughout a surprisingly large coverage of subcutaneous tissue.

If you have discovered a site that appears to be weak, cool/cold, and paler than the surrounding tissues, gently press into the site with your index and middle finger tips or just with your index finger, if there seems only a small passageway open to go deeply into. Gently press into the epicentre of the weak tissue and feel for further indicators of deficiency. As you penetrate deeper, you may find that the coldness and weakness of the tissue becomes even more obvious. At a level where the fingertips have penetrated about 2-3cm (one inch) into the flesh, halt and feel for any sensation. In Alain’s case, I left the position of the fingertips at this depth and within seconds I could feel coldness from still deeper levels contact my fingertips. At this depth, also shift the fingertips from side to side to examine the integrity of the surrounding tissue. In Alain’s case there were thin hard bundles of elongated tissue fibre, like guitar strings, almost floating or suspended within very poor tissue tone. Serge Paoletti (2011) in his excellent book Fasciae: Anatomy, Dysfunction and Treatment, even drops his astute osteopathic speak by calling this “unhealthy” tissue; it does indeed feel pathological, so I go a bit further even and describe it as “sick” tissue. In Chinese medicine such tissue collapse is understood as qi deficiency with accompanying cold and blood and yang deficient sinews. The qi and blood deficiency with coldness causes muscle tissue to atrophy, while the hard contracted bands are consistent with the influence of cold and a lack of yang-blood.

It was only after treatment that I heard from Alain that this precise area had for many years been susceptible to cold (and wind). He had learnt to avoid it and described the feeling of air-conditioning as “deadly… and goes like a tight stream straight into the weak area”. This confirmed that the principal site of deficiency had been correctly determined, as externally generated cold (and wind) always invades the most vulnerable opening. He added, “That muscle area that you treated always felt weak and empty. When I poked inside, it felt like there was nothing.”

Immediately after the treatment, Alain commented that his arm felt so much better. The other practitioners in class, including acupuncturists, shiatsu and remedial massage therapists and a physiotherapy student, agreed they could see a noticeable change. No longer was the area recessed into the body. The class members then felt for changes. Whereas only 10 minutes earlier, the site was empty and cold with easy access to its depths, now the structure of the tissue had changed remarkably. It felt full, warm and healthy, without giving the ready opportunity to penetrate to the depths as before.

A month later when I spoke to Alain by phone, he pre-empted my reason for phoning by declaring: “My whole shoulder feels fantastic and not at all like it used to feel. The area has maintained the same level of integrity as after treatment and it feels free and strong.”

Step by step treatment

The following is the treatment procedure accompanied by brief explanations, precedents of application and method and anecdotes as they apply to each step. The progress of the treatment went in five stages as follows:

- Hot-pressing cupping (yun guan).

- Medicinal cupping (yao guan).

- Withdrawl cupping (xie guan).

- Very light flash cupping (bu guan).

- Warm and close the exterior.

Step 1: Hot-pressing cup (yun guan)

Rationale: The surface is the domain of the yang and the wei qi. Heat has the dynamic and transformational ability to restore and consolidate. We need heat at stage one to recover the yang, mobilise the surface and assist the cup in lifting those pathogens lodged deeper within the yin. Warming the skin and subcutaneous layers will also facilitate the uptake of the medicinal liniment (as in Step 2).

Preparation: The practice involves heating the exterior surface of a glass cup from the inside. I use a type of glass cup that is manufactured in Vietnam. The main body of the cup is thinner than cups produced in China, and the lip is also quite thin, smooth and nicely curved. The comparative thinness of these cups allows me to efficiently heat the inside of the cup, which then radiates to the external surface. The curved glass is very smooth and even, so the surface can be used as a heating massage tool to good effect.

Soft placement of a tonification cup on the deficiency site.

Thai clay pots for cooking that double as hot–pressing implements, sitting on top of furnaces.

Procedure: A flame is introduced inside the cup and held there while the operator twirls the cup around with the other hand. At intervals (after every few seconds), remove the flame and turn the cup around and return the flame again into the twirling cup repeatedly, until the heat has conveyed throughout the cup’s entire surface area. The practitioner must check that the level of heat is not so extreme to cause discomfort or a burn.

Comments: As I have never seen or read about the technique of heating the cup surface to then use as a warming instrument, I call it the “hot-pressing cupping (method)” or yun guan (fa). I have coined this name because it is a modification of an ancient method of hot-pressing (yun) first described in the Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts (MMM), which were written circa 168 BC and discovered within tombs in Hunan Province in the early 1970s. The Chinese character yun means an iron used to press, to take the creases out of material. The character has a fire radical, which designates heat as being essential to its modus operandi. Therefore it is the use of a heated implement or object that is pressed down onto the body. Judging from its frequent recommendation for employment in the MMM, hot-pressing played a significant role in the therapeutics of its day.

One example is the use of heated oblong stones that have been “quenched in vinegar and then used to hot press” (Harper, 1998, p. 97). This is interesting as well because it is a predecessor of sorts to Step 2 to follow, which combines heat with medicinal fluid, or in our case, following heat therapy with the application of medicated liniment.

While in Vietnam I was told of a modern context for this ancient therapy as well. During the Vietnam War, those Vietnamese soldiers in the jungle in the grip of malaria and chilled to the core would lie on heated stones and have them placed on top of their body as well.

Another variation of hot-pressing in the MMM requires an iron pan filled with “scorched salt” when used for therapeutic purposes – otherwise in ordinary life, the same pan was filled with hot coals for ironing. It was used “when an ailment first lodges on the surface of the body and has not penetrated deeply inside” (Harper, 1998: p. 229). I interpret this as not going so deep as to penetrate the organs.

In the province of Isaan, in North-Eastern Thailand, I have seen heat conveyed into the body using a clay pot half filled with hot salt, which is then pressed on specific sites and points. One of the functions of this method is to warm up a woman after her body has become cold following childbirth.

Yun also denotes “moving” like one does using an iron over material. So too with a glass cup, it needs to be shifted and rolled on the skin surface and not left in one place long enough to scald.

It would be rather amiss not to mention that, to date, the first textual evidence of cupping in China is to be found in the Mawangdui texts. Cupping is referred to as “the horn method”, which testifies to hollowed-out animal horns being used as cupping instruments (a).

Other places especially prone to coldness that benefit from the heat-pressing cupping method include the lower lumbar region and the sides of the hips which, especially for women, can be icy cold. Heating a glass cup and allowing warmth to penetrate for five minutes is very soothing. The heatpressing cup does not stay active for very long, so reheating the cup at intervals is necessary. An additional use for the heatpressing cup is to use it as an anmo massage (pressing and rubbing) tool to penetrate heat into points and cold areas. The heated cup can be pressed into a point or a region of deficiency with accompanying wind/ cold/dampness, and rolled over to spread heat over a broad expanse of surface tissue, or slid along any channel to clear blockages and move stagnation.

Compared with some other heat sources, the heated cup is ideal. Contrast it with a popular alternative such as a wheat bag, for example, which when heated in a microwave oven requires that a glass of water is also present to prevent the wheat from igniting. Wheat when heated any way sweats, so these two fluid aspects give wheat bags the dubious distinction of being hot and damp!

The closest resemblance I have seen to the practice of heating cups in the Western cupping tradition was in Shiroka Laka in Southern Bulgaria, when I studied with Maria Peevska, the small town’s respected cupping specialist. Maria would always line up her cups along the hearth of her fireplace to have them nice and toasty before treatments. In China as well, cups are often perched on heaters to get them ready.

Step 2. Medicinal cupping (yao guan)

Rationale: To draw the blood and yang to the surface with light flash cupping, and then apply a herbal liquid to benefit tissue repair and eliminate cold. Cupping is performed to open the skin pores to improve uptake of the liniment.

Procedure: With the same heated cup, perform 3-5 applications of light flash cupping. I will go into a more detailed description of the light flash cupping method in Step 5.

Liniment application: Stretch out a cotton ball and dab the liniment on it. This will allow you to control the liquid rather than give it licence to dribble. Squeeze out some liniment onto the skin, and using a suitable massage technique such as circular movements with the heel of the hand, work the liniment into the focus area.

Comments: Using herbal liniments in association with cupping is not new. This is my adaption of the medicinal cupping method (yao guan). At the Shanghai Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, I was shown cupping equipment that allowed herbal liquid to be fed, via a tube, into the interior of a cup that was already adhered to the skin. This injury medicine, being herbs decocted in water, absorbs into the skin while the cup is active. The cup’s effect of opening the skin pores facilitates an increased absorption and uptake of the herbal liquid. I was also instructed in other ways of performing medicinal cupping. Dr Zhou taught me that people employ the simple practice of boiling bamboo cups in either ginger or chili juice, mixed with a sufficient amount of water, and then apply them to rid coldness and relax muscles especially during the cold weather. Another method is filling a cup about one quarter full of liniment such as Zheng Gu Shui, and turning it onto the skin quickly enough so the cup is secured with the herbal liquid inside.

Combining the two can also be found in traditional practices from other parts of the world. Zenon Gruber MD, one of my cupping students many years ago, said that rubbing a little chili based cream called Finalgon into the centre of an area immediately before cupping over it was the most popular and available way of dealing with aches and pains during World War II. Zenon remembered in his own time the dreadful experiences that the Polish people had to endure during those long Polish winters and said that Finalgon, by its association with cupping, was “so valued that people would barter for goods with it in preference to money”.

“Other places especially prone to coldness that benefit from the heatpressing cupping method include the lower lumbar region and the sides of the hips which, especially for women, can be icy cold.”

External herbal treatment: The herbs in this formula are soaked in alcohol, which also has the characteristic of being warm and therefore aids in reconstructing the yang, and is essential in nourishing the ying qi to repair deficiency syndrome at a fundamental level. In addition, using alcohol as a medium has the two-fold benefit of drawing out the active ingredients of the herbs and, when it is rubbed into the skin surface, the warming nature of the alcohol opens the skin pores, which allows the formula to be conveyed into the depth of the injury. To prepare the liniment, the herbs are soaked in alcohol in a clay pot and left to steep for at least three weeks.

My general purpose formula, which I call Fascia Strengthening Liniment, is detailed at the bottom of the page.

As this treatment stage involves three benefits, being heat, cupping and the application of external injury medicine, analysts could argue that the same improvement might be gained without the tonifying cups. In my opinion this would be impossible. I have experimented numerous times with singular applications with each of these three and am convinced that the cupping component is very significant. As a combination they are an exponential gain.

Step 3. Withdrawal cupping (xie guan)

Rationale: Long-term injury has pathogens lurking deep inside. These need to be withdrawn.

Procedure: Apply a number one or number two strong level cup directly on the weakness area to draw out deep-seated cold and other accompanying pathogens lodged inside. Provided it is just a point or small area, a small cup is advised. Otherwise larger cup sizes are needed to cover the site of deficiency. If it is a line of weakness, then two or three cups close together should be employed.

Comments: A strong cup has the benefit of withdrawing pathogens and dispersing blockages. Due to the strength of the vacuum, it can reach down deep into the tissues and extract the long-term causes of stagnation and pain. However, it is imperative that the cup not be left active for longer than three minutes, otherwise it will become a reducing method, which will further weaken the tissue and exacerbate the deficiency. The goal is to pull out deepseated pathogens while not allowing the cup to produce a reducing or sedating effect, which will happen if the cup is left for more than three minutes. This withdrawing of deleterious pathogens is essential in the process of recovery. If this stage is neglected, the pathogen(s) remain inside, only to be covered by the fortification of the exterior with light flash cupping.

When I was studying and practising at the Guan Yin Hospital (1978-80) in Taipei, my tuina teacher, the Buddhist monk Da Ti, taught me a variation of this practice, which has a very powerful effect of ridding the entire body of cold. He first placed a strong cup for three minutes over the navel. After removal of the cup, he would fill the navel cavity with salt and burn nine cones of moxa, followed by a further nine cones if necessary. He would ask the patient if they felt warmth permeating through their body. After cupping the navel, Da Ti explained it was essential to close the navel opening with heat, otherwise it was harmful to the store of yuan qi. One of his favourite sayings was qi xu ze han or “when qi is deficient, there is cold”. At the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Dr Zhou also spoke to me of literally “pulling the good qi out” if there was already deficiency and a strong cup was left for too long.

Step 4. Light flash cupping (bu guan) Rationale: Warm the yang and tonify the qi and blood to dispel cold.

Procedure: Stage 1. Using the same warm cup, restore heat inside and apply gently to the focus location. As the cup adheres to the skin, pull (draw) it softly away from the surface, thus lifting the suctioned skin, and repeat 5 – 9 times. This light drawing out from the pull of the cup is to arouse the qi and blood. Each time, very gently release the vacuum and repeat.

Stage Two. Reapply the heated cup gently but hereafter don’t draw on the cup. Instead after each soft placement, wait and carefully watch for the patient’s breath to arrive at the cup. The soft warmth and gentle placement of the cup will lead to an awareness of the cup and how comforting it feels. This in turn will nurture the breath to travel to the cup, which in turn guides the qi to restore tissue integrity. As the breath arrives at the cup, carefully observe with each inhalation, how the cup rises. The peak of the in-breath is the apex of the yang. At this moment of every application, remove the cup so gently that not even a hiss of air leaving the cup can be heard. Repeat a sequence of nine. This is the subtle essence of cupping tonification.

Success with tonification cupping is achieved by heat and soft repetitious cupping, where the cup does little more than kiss or softly caress the area, to coax and nurture the qi and blood to fill the spaces between the skin, the subcutaneous tissues and the deeper flesh. If it doesn’t sound like a method with powerful rehabilitative consequences, I can assure you that soon after treatment, a deep feeling of rejuvenation is experienced.

On the ninth application of the final light flash cupping application, leave the cup stationary for a maximum of 10 minutes. Be sure to cover the entire body with warm towels or similar.

Comments: The more commonly practised version of flash cupping ( shan guan) is performed fairly strongly and is therefore a reducing or dispersing method. Performed lightly it is a powerful tonifying method (bu guan). The softer the cup, the more profound the nurturing effect.

“If it doesn’t sound like a method with powerful rehabilitative consequences, I can assure you that soon after treatment, a deep feeling of rejuvenation is experienced.”

A word on therapeutic numerology. In medicine and yang sheng (nourishment of life) practices such as Ba Duan Jin and Yi Jin Jing, it is advised to practise repeated sequences in sets of nines. In ancient China, nine was deemed to be the highest primary number to which humankind could aspire. Ten ( ), written in Chinese as an equalsided cross, signifies the four cardinal directions travelling to infinity (Heaven). But because humankind is bound in this mortal coil, the highest that a person can aspire to is nine. Even the emperors were limited to ordering things in nines – being “only” the sons of Heaven. The emperors also had nine dragons embroidered on their robes. Heaven is above, and therefore yang, so the number that comes closest is also the most yang. The ultimate glory of nine is in the multiplication of nine times nine. The Yi Jing or Book of Changes is based on a total of all possible natural configurations found in nature and the universe. Each change is represented by a trigram or different code of broken (yin) and unbroken (yang) lines. The total for the entire system adds up to 81.

Step 5. Warm and close the exterior

Rationale: Apply one final application of the Fascia Strengthening Liniment or similar to further consolidate the yang and nourish the tissues. The alcohol in the liniment is also astringent, and will assist in closing the skin pores to keep the warmth inside. Warmth in more ways than one is always a good thing.

Comment: After treating with cups, Maria Peevska, the village cupper in Bulgaria, always rubbed a mixture of iodine and alcohol over the area treated to “close the skin pores and keep the body warm for a long time”.

A final thought

Soft cupping to tonify deficiency can be a challenging concept, whether one is born into an Eastern or Western culture. I have seen a fair share of practitioners taken aback, even confronted, by the remarkable changes that can happen, even though the precedents for this refined approach are all there in Chinese medicine. As a quote from Ye Tian–Shi, also posted as the final line of a Lantern editorial (2007) whispers: A light intervention can eliminate a deepseated problem.

Footnotes

- (a) It is a rather unglamorous cameo, however, featuring its efficacy in drawing out a haemorrhoid, so it can then be tied with string at its base and lanced.

- (b) Herb function descriptions from Bensky, Clavey and Stoger (2008): Materia Medica.

Bibliography

- Biel, Andrew (2010): Trail Guide to the Body. Canada: Books of Discovery Bensky, Dan; Clavey, Steven and Stoger, Eric. (2004) Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica. 3rd Ed. Seattle: Eastland Press.

- The Lantern (2007). Vol. 4. No.1. Harper, Donald John (1998) Early Chinese Medical Literature: the Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts. London: Kegan Paul International.

- Paoletti, Serge (2011) The Fasciae: Anatomy, Dysfunction and Treatment, Seattle: Eastland Press.

Fascia Strengthening Liniment (ingredients) (b)

- Ai Ye (Artemisiae Argyi Folium) – warm, dispels cold dampness, stops pain due to cold.

- Chuan Xiong (Chuanxiong Rhizoma) – warm, moves the blood and promotes the qi, disperses blood stasis.

- Nui Xi (Achyranthes bidentatae Radix) – neutral, disperses blood stasis, strengthens sinews and bones.

- Rou Gui (Cinnamomi Cortex) – hot, warms and tonifies yang, disperses deep cold and warms the channels.

- Gan Jiang (Zingiberis Rhizoma) – hot, unblocks channels, revives yang and expels cold, disperses cold qi in all channels.

- Gui Zhi (Cinnamomi Ramulus) – warm, releases the muscle layer, unblocks yang qi, releases the exterior, warms and unblocks the channels and collaterals, for windcold-damp obstruction, expels wind.

- Xu Duan (Dipsaci Radix) – sl. warm, promotes movement of blood, alleviates pain and reconnects the sinews and bones. Literal English translation: reconnect what is broken.

- Du Zhong (Eucommiae Cortex) – warm, strengthens the sinews especially the lower back and knees, aids the smooth flow of qi, and with Du Huo especially dispels local coldness exacerbated by exposure to cold.

- Du Huo (Angelicae Pubescentis Radix) – warm, dispels wind, dampness and cold especially in the lower back and legs, for acute and chronic disorders, tracks down lurking wind.

- Qiang Huo (Notopterygii Rhizoma Seu Radix) – warm, very effective for dispelling wind with a focus on the upper and more superficial aspects of the body.

Bruce Bentley studied Chinese medicine in Taiwan from 1976 until 1981. He has a Masters Degree in Health Studies based on his thesis entitled Cupping as Therapeutic Technology. He has investigated the Eastern tradition of cupping in Vietnam, and studied at the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Tibetan Medicine Hospital in Lhasa, Tibet, and at the Uighur Traditional Medicine Hospital in Urumqi, Xinjiang Provence, China. To research the Western practice of cupping, Bruce visited the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra where masseurs employ cupping to treat injuries and enhance performance, and in 1998 he went to Europe and North Africa, doing archival research on cupping at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London, and the Department for the History of Medicine at Rome University, followed by field-work in Sicily, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey, Morocco and Tunisia learning local cupping traditions. Bruce’s most recent research trip investigating cupping was in Cambodia during July 2003. He is also a state registered acupuncturist and Chinese herbalist and director of Health Traditions: www.healthtraditions.com.au.

Top ↑