There are at least five reasons why cupping is an authentic fit for community health care services in developing countries. First, the instruments are inexpensive. Second, provided good instruction is at hand, learning to apply them safely and effectively to treat common illness and pain conditions does not require long study. Third, cupping vessels, especially silicone and vacuum pump sets, are lightweight, sturdy and easily transportable. Fourth, for people connected to traditional ways of thinking, cupping’s ability to draw out pain factors has a culturally rational basis. Fifth, the choice to perform a time-honoured therapy such as cupping, which has for generations proven itself to be a safe practice, should be an inherent human right.

Mount Meru District Hospital Teaching Assignment

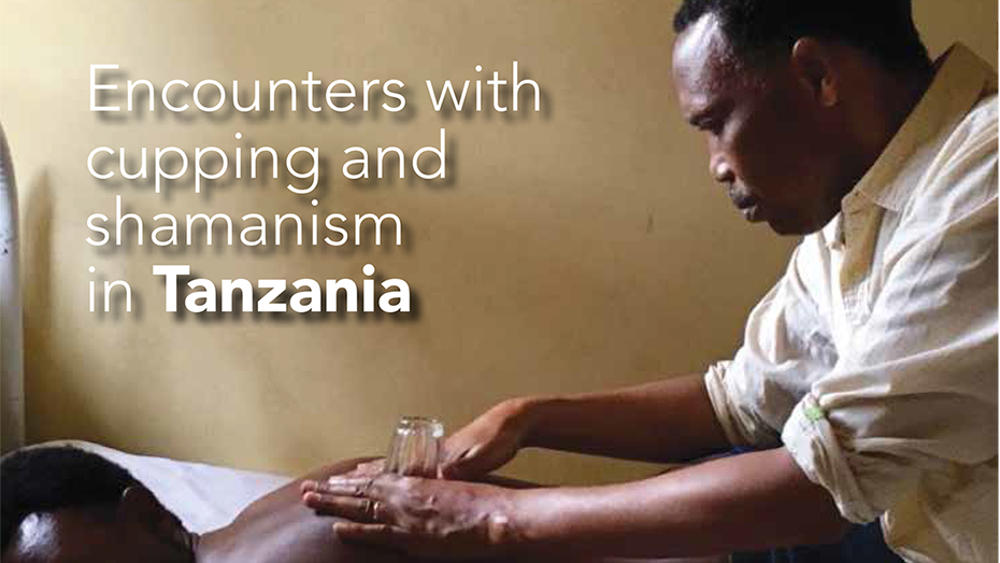

In early 2016, for those reasons and more, I accepted an invitation to northern Tanzania to instruct a group of doctors, nurses and physical therapists in cupping (and a little gua sha) at the Mount Meru District Hospital, on the outskirts of the city of Arusha. The course went for six hours a day for four days. When I spoke to Dr Ukio Kusirye, the hospital’s director, about the assignment he said, “The purpose is to train interested medical workers in cupping so they can bring this method into their practice and improve people’s health.”

On day one I invited those attending to share their thoughts on African traditional medicine (dawa za asili zai kia fruka) and health care. Dr Kornel Huyas, who is in charge of a village based branch of the hospital, said it was the custom for women who had undergone caesarian section to cover their lower abdomen with a heated towel to bring warmth to the area and reduce any recurrence of pain. He added, “During cold weather women wrap multiple layers of cloth around their waist to prevent coldness (baridi) from entering their bodies and chilling their kidneys.” There was consensus among the participants that traditional medicine was a valuable legacy to be appreciated and combined with modern medicine.

I talked briefly about cupping’s history, its rationale and diagnostic features, its broad-spectrum treatment benefits, and its relationship with traditional and modern pain and illness etiologies. Participants were asked to list some conditions that they frequently dealt with and then we considered whether cupping might be of value. This was important for me to know, as I wanted to learn how I could connect with local health concerns and match them with practical treatments. During the program, I also tried to meld traditional ideas about cupping from other cultures with the African understanding, while also adjusting these to language that was compatible with clinically defined presentations. Finally, as the class progressed, I made time to deal with treatment requests such as headache, cough and menstrual discomfort. In response to further queries, I also treated discomforts that the participants might be suffering, not only to help them out but to give them a first-hand experience of its efficacy.

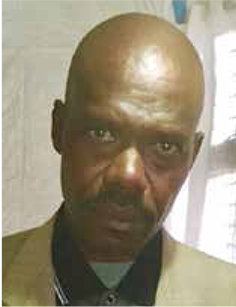

One such call came from a doctor who had nagging soreness in his leg with pronounced pain around scar tissue left following an impact injury caused by a tree falling on his leg when he was boy. He said he was constantly bothered by the damage and so, while everyone watched, I set about explaining and performing a suitable treatment (below, right). Following on, he reported his leg felt comfortable, and for the remaining two contact days he said it was pain-free for the first time in almost 20 years.

Fieldwork and research methods

At sunrise on the day after completing the hospital teaching assignment, together with my translator Dr Juma Rashid Alfan MD, a hired driver and an all-terrain vehicle, we were ready to go to the Singida region, a large area of Central Tanzania that the Lonely Planet (2015: 211) travel guide to Tanzania describes as “well off the tourist itineraries”. We had agreed it was likely to be a good place to go in search of traditional medicine practitioners. Beforehand Dr Juma had kindly arranged some meetings.

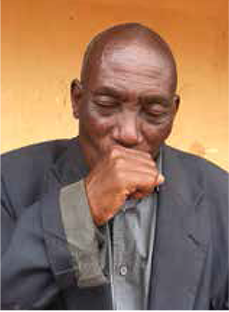

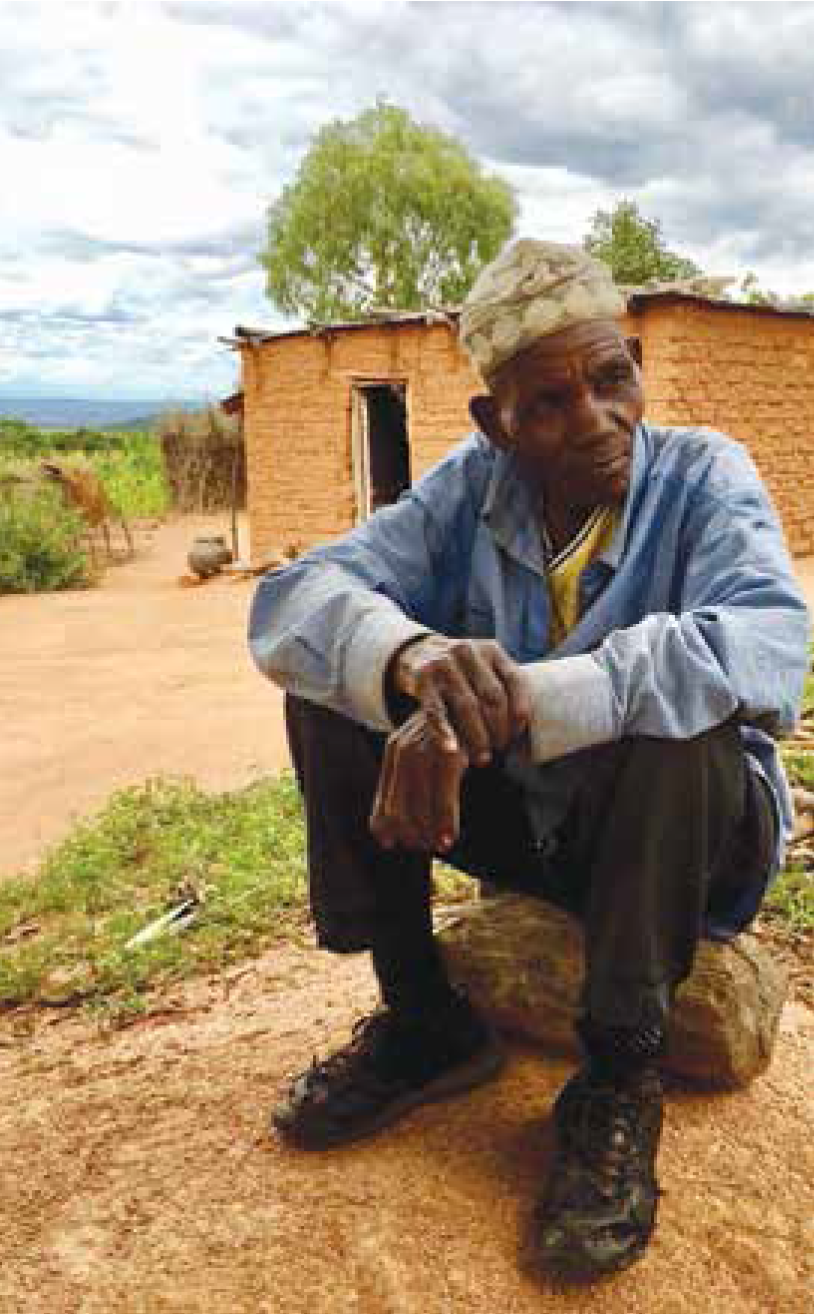

My focus was to learn what I could about traditional cupping (kuvuta). This part of the fieldwork lasted for five days and I managed to have in-depth discussions with three practitioners. Getting there and back was virtually a day trip both ways. Once we had arrived in Singida, we did go out of our way following other leads, but these proved fruitless. While on the road to our first interview, we stopped at Nkurigi Village to ask for directions. We got talking to a friendly man named Ibrahimu Abdalah Nkumbo of the Nyiramba tribe, and I asked “do you know about cupping?” His reaction (right) says it all. He was demonstrating the ancient method of sucking at the tip of a hollow vessel (presumably an animal horn) to perform treatment.

When time came to return to base, I was still eager for more. On the way to and from Singida, I’d noted that about 10 km outside Arusha was a town named Kisongo which was mostly populated by Maasai tribespeople, who are easily recognisable wearing their traditional shuka (shawl). Previously, in the two days I had in Tanzania before starting teaching, I had been fortunate to meet with a Maasai herbalist, who told me that cupping was a part of his tribal tradition. So after a short break back in Arusha, I made an exploratory day trip to Kisongo to see if I could make any contacts. Early that morning, I hailed a local mini bus called a dalla-dalla, and with everyone crammed on board like sardines, went there. Seeing as it was early and I had time to spare, I decided to explore the local bush for a couple of hours and do some birdwatching at a nearby lake. In an utterly unexpected manner, I chanced upon Efata Ngida Roine, a Maasai man grazing his herd of goats. I told him about my interest in speaking with healers who were practising cupping and he kindly went off to arrange a rendezvous. He returned saying to meet him in town the following morning. I returned the next day with Magdalena Samwel, a member of the Fyomi tribe, as my translator. I was fortunate to have met Magdalena as my guide when I visited the Natural History Museum on my first day in the country. Her cultural knowledge, translation skills and ability to effectively win the confidence of the Maasai were critical.

Ibrahimu Abdalah Nkumbo

Performing cupping to a chronic leg injury. Note the visible indentation of scar tissue in the midline of the reflection of light.

Setting the scene

The following is a brief account of my experiences and the information I gleaned from the five cupping practitioners I met. With their consent I used my iPhone to voice record each interview, which I later transcribed word for word, so as to not miss out on any details. This is important, especially when cross-referencing information is called for. As a matter of course, I also asked permission to take photos and write about what I had gathered. All was happily approved.

Fieldwork is always a gamble and I feel that somehow random meetings and coincidences often produce striking opportunities, even when compared to pre-arranged scenarios. I have faith in unanticipated turns of events, though of course the pursuit of the goal and going out of one’s way to make contact is a prerequisite—otherwise no one is the wiser about your aims.

I also tend not to work off a tight list of set questions, although to get a handle on the transmission of each person’s knowledge and to get the ball rolling, I always begin with, “Who taught you?” After many years of doing such interviews, one needs a platform to work from and an aim to achieve, but to follow a stock regimen of questions is far less interesting than following the drift of the content that arises and then to delve deeper. The best discussions are always when the process is an unfolding one.

It is important to note that I have called the first two practitioners I encountered, “shaman/healers”. This is because in their practice they employ naturalistic and supernatural methods of curing. Often, although it did not occur in these instances, there is no divide between the two, and indeed it is not uncommon to combine both approaches when the practitioner believes it serves the needs of the patient.

The reasons why I was so keen to explore cupping and its social relations in Tanzanian traditional medicine were, firstly, that there has generally been so little interest given to traditional African medicine. Secondly, like a bad hangover that persists to this day, African traditional medicine has been fraught with misunderstanding and cultural bias. Instead of investigating its essential truth in weaving each person back to health through an intricate emotional, spiritual, physical and social therapeutic process, it has too often been condescendingly portrayed as “mumbo jumbo” in the hands of witch-doctors, thus making it seemingly so alien that it becomes immediately negative and unapproachable in comparison to the reality of its deep intent, which I was about to discover.

The interviews

Zainabu Msakuu Misanga

Zainabu Msakuu Misanga Female, born 1952.

Interview: July 6, Singida region.

Zainabu Msakuu Misanga is a shaman/ healer (uponyaaji wa mizimu) of the Unyanga tribe from the East Singida region. She treats her patients in separate rooms beside her family home. Zainabu said she inherited her talent to heal from her grandfather, and added, “People have told me he was so powerful that he could sneeze and make a tree fall over. I was in my mother’s belly when he died. He was 120 years old. He passed his knowledge on to me. I also continue to receive regular instruction from my other ancestral spirits. They were the ones who came to me in dreams and helped me find my way when I was in trouble.” I wanted to pursue this comment in more detail, because it often appears that in the lead-up to taking on the role of shaman, many initiates have previously had more than their fair share of angst and difficulty, or have at least suffered some significant physical or emotional discord. This was a common theme among the shaman I encountered in Asia, and it was no different for Zainabu. She was partially paralysed and unable to walk from the age of five, and confined to a wheelchair for 20 years. She then began to feel her legs and was able to walk again, but in her own words, “I started acting crazy.” This went on until a shaman she had contact with told her that she was meant to become one of their kind. I mentioned to her that many, though not all, the shaman I had encountered, in Thailand for instance, had a similar tale to tell. Often, before finding their true path, they were either desperately unwell or had a history of “anti-social” behaviour. One suspects that too often in such cases in the West, psychiatry is liable to diagnose people in this predicament as psychotic, and give them drugs to take. However, here, as in Thailand, she found a path and the opportunity to express herself, and in doing so was cured in transit. In the next interview, the female shaman/healer also speaks of a comparable passage to practice.

I observed Zainabu treating two patients. The first was a one-week-old boy brought in by his mother. He had been in constant emotional distress with no sleep since birth, although he was feeding well from his mother’s breast. Zainabu said her ancestral spirits had come to her in a dream the night before and told her about the baby and the cause of his anguish. She explained to the mother that the source of her baby’s problem rested with him being named by his father, incorrectly, instead of being named by her. Hearing this the mother promptly asked for her son’s name to be changed at a short ceremony, and following some additional special healings, including rubbing ash into his umbilicus, he immediately slipped into blissful repose for the first time, and remained that way for the next three hours while I was present.

This, it is easy to gather, is not naturalistic medicine based on occurrences of the natural world. It is more a journey into a broader social universe, earmarked for the sake of categorisation to be “supernatural” medicine—where illness is due to otherworldly or “inexplicable” causes. It is a realm of medicine that considers emotional and social harmony on equal terms with the physical health of the individual. All supernatural therapeutic interventions fulfill an unequivocally profound task—they step in where there is a fray in the social weave of community life and group wellbeing. Illness then becomes a condition the individual must bear until that fray is mended. The shaman’s role is to figure out how to best intervene, reknit the fracture and reestablish the mores and best interests of the child with the community (and ancestors). It is ancient primal stuff that probably laid the basis for humans being able to successfully co-habit. Such insights could be what is needed now to deal with many of the ills of the modern condition.

Zainabu treated the second patient in a decidedly naturalistic manner. The patient explained to me that she had suffered continual pain for 18 years, and this was her fourth weekly treatment by Zainabu. She had previously seen an array of biomedical and traditional practitioners, and tried many therapies without success. She said that since her first treatment, she had experienced no discomfort and was smiling again. In the lead-up to her treatment, Dr Juma and I were impressed by her thoroughgoing diagnostic examination, which included extensive palpation throughout her patient’s troubled areas. She wrote all her findings down in a notebook. When this was completed, I couldn’t help but ask Zainabu, and then her patient, if I could feel her pulse and inspect her tongue. Her pulses in the middle jiao, related to the Gallbladder/Liver, were deep, slow and tight. Her Spleen/Stomach pulse was tight, thready and slightly elevated. Her tongue was slightly pale with a blue hue evident throughout the mid-body, being the Spleen/Stomach section, with a thin white coating and multiple horizontal cracks throughout the midsection extending into the Lung region (top). Her inverted tongue showed blue veins indicating stagnation. In my opinion this indicated a pattern of deep internal coldness and Stomach/Lung yin deficiency. In practice I would work from the treatment principle: dispel cold and harmonise the middle.

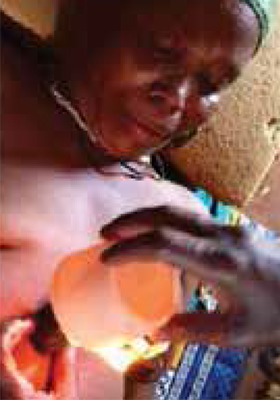

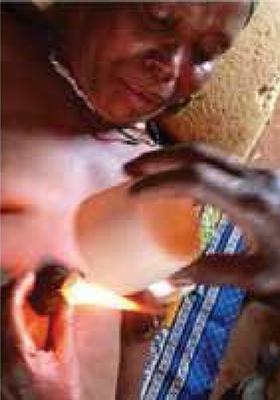

Zainabu’s treatment was to apply a single cup over a specific location I soon came to realise was the most esteemed and common place to cup for all the practitioners I was to meet. I have no idea if this is a broadly held belief in other countries or areas in subSaharan Africa, but it was paramount here. It is the body region called chembe ya moyo in Swahili, or choghombe in Zainabu’s tribal Kinyaturu language. Dr Juma translated chembe ya moyo to be the xiphoid process, being the inferior segment of the sternum.

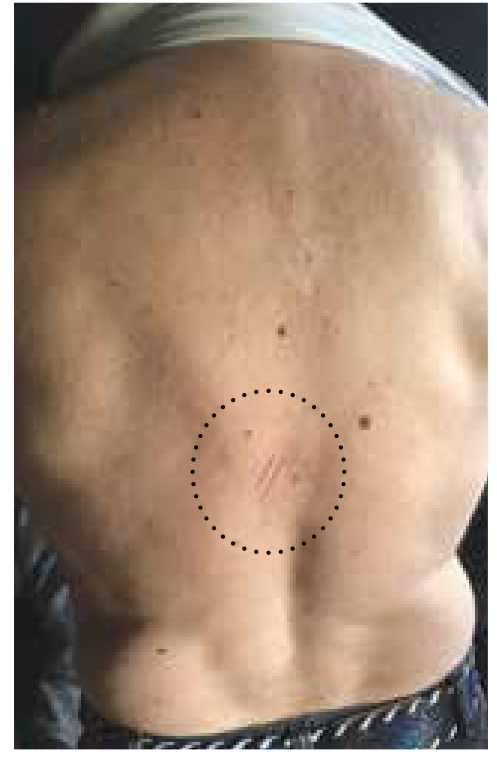

Area cupped in conjunction with chembe ya moyo.

In modern medical terms, xiphoid pain is called xiphoidalgia. It is a musculoskeletal disorder that (although often overlooked) can be the cause of chest, epigastrium and back pain, nausea and vomiting. Anatomically, the superior margin of the liver lies underneath this landmark, and close-by to the right is the lower portion of the esophagus before it narrows at the lower esophageal sphincter and connects with the upper part of the stomach. Some signs and symptoms related to disorders of the upper epigastric zone include a burning, cramplike pain that can radiate to the back or the right shoulder. Maladies include stomach ulcer, epigastric hernia and heartburn and indigestion. Interestingly, the xiphoid process lies level with the ninth thoracic vertebra. In an interview to come, I asked Dr Sabaya Lengobo Kileo, a Maasai cupping specialist to mark the location on my back where he performed wet cupping to a specific location on the back in tandem with (dry) cupping chembe ya moyo. He drew the two lines (far left) to the left of the ninth thoracic vertebra.

According to Zainabu, discord within chembe ya moyo accounts for many health problems, and includes local pain, nausea, loss of appetite, lethargy, menstrual pain, and not least it is the principal cupping location to “pull pain out from anywhere in the body”. She also made a point of saying that pain can radiate from chembe ya moyo and extend across the line of the diaphragm to the diametrically opposed posterior position on the spine. She showed me where this was and touched the T8 and T9 area of my back. She added, “It also withdraws pain caused by bad diet.”

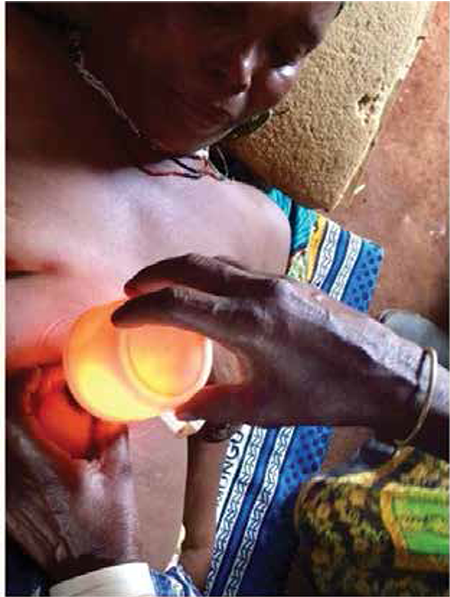

The sequence of photos (above) features an ordinary plastic drinking cup being applied to chembe ya moyo. She is using this plastic cup because her hollow cupping horns were on loan to a friend. Out of interest, I inquired how she applied cupping horns. She instructed, “First put a soft mass of wax on the skin, cover it with the wide end of the horn and suck it up quickly so it stops the hole at the narrow tip.”

The black bundle (top right) is cloth filled with sand and herbs appropriate for her patient’s condition. The four corners of the square material are drawn together with enough left over to twist into a wick. This wick is then dipped in kerosene and lit. The patient said she felt the heated sand and herbs penetrate into the area during the treatment. It was placed on the xiphoid process to pull the bone outwards when it was suspected that it has been drawn inwards by the contractive nature of coldness—being one of the major explanations for the adverse repositioning of this bone. I asked why this location was so important. She replied, “The xiphoid bone and the area underneath it is a very important part of the body for many functions including both the female and male reproductive organs.”

I asked her what was the purpose of the cup used in today’s treatment. She replied, “It brings the blood, pulls out coldness and pulls the bone back to its correct position. This change to the position of the bone can be caused by cold weather and coldness inside.”

Aisha Shabani Mkenga

Aisha Shabani Mkenga Female, born 1955.

Interview: April, 7, 2016, Singida Region.

Aisha Shabani Mkenga (top) of the Wanyaturu tribe, practises in a room in her extended family’s mud residence, deep in the countryside. Without a 4WD vehicle we would never have been able to manoeuvre along the roads that would be best be written in inverted commas.

Aisha learnt her healing practices, including cupping and herbal medicine, from her father who was also a shaman/healer.

Her path to becoming a practitioner had been arduous. She spoke of how as a teenager she went through her “crazy” time, even taking off her clothes many times and running around naked in her village. Then another shaman identified her as someone who needed to become a shaman and with her parents’ permission she underwent a ceremony that transformed her. Why does it seem that a person needs to go through a lengthy episode of personal discontent and fracture before finding one’s true calling? She answered, “It was all about the ancestors preparing me to become a shaman/healer. That’s what the ancestral spirits do. They change the person’s mind, personality and behavioural traits. When this happens, the person responds and starts doing unusual things. Such reactions are an alert to other shaman and regarded as a preparatory stage. It is the beginning of change. It is a time of opening up a person’s mentality… and until that time when she or he comes to terms with this change and gets a new understanding, she or he will be confused within themselves and ask, ‘why is this happening to me?’ It is like the sort of situation that most sensitive inquiring young people ask themselves; but it would appear that the experience of change in this circumstance is even more dramatic and confronting compared to the changes that “regular” people experience. I queried whether this was how she would explain it. Aisha answered, “Precisely! In my case it was an indication that I needed to develop other skills beyond normal activities to best reflect what I was capable of.” My next question was: “Are you now comfortable with yourself?” She answered, “I don’t have any problems any more,” and laughed, “Even when there’s a shaman’s meeting, I am invited early by the organisers and well received.” I then asked, “Do you feel you experience a greater kind of happiness than most others?” She kept it professional by answering, “The local community doesn’t bother me and they are happy I live here. If they get a problem, even at midnight, they know they can visit me and I am ready to help. Even some doctors and nurses from nearby clinics come to see me because they understand that some diseases cannot be successfully treated by them. They also refer difficult patients to me.”

One eye-opening aspect of her cupping practice was her innovative use of a rubber ball. She had sliced off a section, and after experimenting with it found it made an effective vacuum device. She said it was cleaner and easier than using her mouth to suck and apply a hollow horn. Her segmented rubber ball cups reminded me of the recently designed and manufactured flexible silicone cupping vessels I often use (Bentley, 2013). She simply applied the rubber cup to the flesh and pressed the top inwards to make it adhere.

Like other knowledgeable practitioners, Aisha is versed in discriminating and diagnosing different types of cupping marks. She is also especially keen on using cups to draw out coldness from the body. She knows to vary the suction strength according to the strength of the person and the nature of their condition. “How long do you leave cups on for?” I asked. She replied, “Usually five to 10 minutes. But if I’m using them to release difficult emotional or spiritual problems, then in my dreams the night before the spirits usually instruct me to leave them on for around an hour to draw out and release what needs to be taken out.”

Aisha Shabani Mkenga and her rubber ball cups

On the naturalistic side of her practice, Aisha uses herbal medicine and said she often performed cupping. She said that cupping drew out pain and spoke at length about applying one cupping vessel over chembe ya moyo—or choghombe in her native Kinyaturu language—to engage the xiphoid process and the upper epigastric region. She explained: “When there is pain due to coldness in the body, which can be caused by weather, and especially by cold drafts, it pulls [contracts] the xiphoid bone backwards [posteriorly].”

When she places a cup over this location, it pulls the bone back into its proper position and pulls coldness, wind and dusty conditions out as well. These she explained “are the three critical atmospheric conditions that can cause illness”. She believes chembe ya moyo is the source of all pain in the body, and being aligned in its correct position is instrumental to the welfare of all bodily functions. “You often need only to place one cup here to benefit all sorts of pains, as well as breathing difficulties and loss of appetite.” Aisha also uses her cupping vessels at other locations to treat coughs and muscle pain that affects the back, arms and legs.

One interesting feature of her practice is her tribal tradition of crushing the fresh leaves of a certain local herb and mixing them with milk, which she leaves to stand for three days to turn into a sort of herbal yoghurt. “When I’m treating muscle injury, I first cup the painful area(s) to warm them up and open the skin pores. Then I rub the herbal yoghurt in and tell the patient to return in two days for another round of cupping to draw all the injury out.”

Hamis Athuman Pumi

Hamis Athuman Pumi Male, born 1939.

Interview: April 8, 2016, Nkinto village, Mkalama District, Singida.

Dr Hamis is a natural healer (uponyaji wa dawa za asila) with a certificate to practise issued by the Tanzanian government. It was spellbinding sitting under a tree and having him apply hollow animal horns to my body (below). These were adhered by sucking at the narrow end and plugging it with bees wax that had been stored in his cheek. When the moment came, he used his tongue to push the wax into the hole at the apex of the horn to block it. When it was time to release the cup, he used a thick pin to penetrate through the wax.

All this took place as I looked into our primordial past across to the Ngoroongoro Crater and beyond to the southern peaks of the Rift Valley. It was there in the Olduvai Gorge in 1960 that the paleoanthropologists and archaeologists Louis and Mary Leaky and their team discovered segments of bone that belonged to Homo habilus (meaning “handy man”), the proto-human species that lived around two million years ago. In the Olduvai Gorge habilus built a stone windbreak, which is identified as the first known human construction.

They also chipped and fashioned the earliest stone tool technologies. It is not far fetched to imagine “handy man” dropping a large stone on his or her finger, and instinctively putting it into the mouth and sucking it to bring some relief—just like we do today. If this did happen, then the first application of “vacuum applied to the skin surface for a therapeutic effect”, aka cupping, could have occurred.

Dr Hamis is foremost a herbalist and mostly uses plants that grow in his locale. His employment of a herb called mdabina, which grows in his backyard, in with his cupping treatments is intriguing. Mdabina is an indigenous shrub that produces clusters of red berries, which he picks, dries and crushes to a powder. This he applies to pain sites. He showed me how he performs this procedure in detail (below).

At a problem site, he applies the powdered herb and makes a cross, with the intersecting mid point directly over the centre of the pain. He then makes a small superficial incision at this point and applies a horn cup directly on top. He told me that mdabina had the ability to draw toxins and other pathogens and impurities from the range of the 360-degree circuit formed by the endings of the four lines.

The purpose of the superficial incision is not a bloodletting/wet cupping method as one might assume. The intention is not to draw blood, but to create an opening for toxins in the blood to exit the body. “The herb and the cup work together to extract factors such as coldness, poisons, and I’ve even seen particles like tiny crystals come out,” he said. “When I treat swollen legs by this method, I often see thick sticky fluid coming out. The patient feels much better afterwards.”

I asked about chenbe ya moyo. “Yes I cup this region for five minutes, two times a day, morning and night,” he replied, “to cure stress, unstable emotions, loss of appetite, stabbing pain in the chest and cough. All these problems can be cured by bringing the xiphoid process back into its correct position, so it is not going inwards.” I then asked, “Does illness pull the bone inwards?” He answered, “Yes, any kind of illness can do this. It can be caused by many factors including adverse climate. This happens especially during the rainy season.”

Levi Ole Lamay

Levi Ole Lamay Male, born 1978.

Interview: April 12, 2016, Kisongo, Arumeru District.

Dr Levi is a registered herbalist who has an office in the township of Kisongo. He began his training with his grandfather at the age of 13. He believes cupping chembe ya moyo is beneficial to make the local area comfortable because it has a special relationship with the digestive system. “This region,” he explained, “is essential for good health because it is the starting point of the stomach. You need this area to be in balance to be healthy and cure digestive illnesses. When a patient needs this treatment, I apply a cup over chembe ya moyo for 45 minutes for three days in a row.” He believes its best effects are gained when the patient is hungry. “After treatment I advise them to eat.” His method of cupping chembe ya moyo is to place a bag of sand and herbs over the region, then light the wick and quickly cover the flame with a glass drinking cup, which he considers easy to clean and most sanitary.

Sabaya Lengobo Kileo

Sabaya Lengobo Kileo Male, born 1972.

Interview: April 12, 2016, Kisongo, Arumeru District.

Dr Sabaya Lengobo Kileo is a specialist Maasai cupper who practises on the outskirts of Kisongo. He believes that cupping is as popular in the Maasai community now as it has always been for “so many generations”. He added, “I have Maasai people even coming from Kenya to see me for treatment.” While I was present, he treated a patient who had discomfort between his scapula by using a clean razor blade to incise the skin, followed by application of a horn cup that he sucked at the tip and blocked to hold it tight to become a wet cupping treatment (below).

I asked Sabaya what were the main problems he treats with cupping. He answered, “mostly soft tissue injuries. They happen to people all the time, and include adults or children falling from trees, and even trees falling on people. They get hurt also when they are hunting or fighting. I also use cups to pull out splinters and thorns and the like.”

I did ask, seeing cupping has been used in other parts of the world for this purpose, if he used them to withdraw poison from snakebite or from wasp or scorpion stings. He answered, “No, there is a special stone we Maasai use that can be tied to a sting or bite which has the ability to pull these different toxins out.”

Sabaya explained that an essential balancing or harmonising of the complete body is be achieved by combining wet and dry cupping to two specific locations.

“First, while the patient is in a seated position, I lightly cut the skin at a special location on the back called eng’orioog (in Maasai). Then I apply a horn cup over it to draw some blood.” This is wet cupping (tsekekwa in Maasai). The location of eng’orioog can be seen at the two fine lines (see Page 36) drawn to the left of the spine and close to T9.

“Once this has been achieved and the horn is in place and active, I go to front of the patient and apply a glass cup [or jar] with strong suction to dry cup chembe ya mayo (tkelivunyekii emuinyaaa in Maasai). The horn cupping vessel on the back removes bad blood (osagee torunoo in Maasai, damu chafu in Swahili), while the glass cup applied to chembe ya moyo withdraws coldness and corrects any inversion that might be occurring to the xiphoid bone. My father told me that the correct position of this bone is important to keep the body stable. You pull out the organ (stomach) that has entered into this bone, so it becomes properly positioned and fresh. If you have not eaten regularly, or have any kind of injury, this bone can go inwards. The combination of wet cupping to eng’orioog and dry cupping to chembe ya moyo is good for any pain throughout the entire body. It cures blood disorders and harmonises the stomach and the diaphragm.While this fundamental procedure is active, it is also possible to apply additional cups to treat local areas of pain elsewhere in the body.”

According to the teachings handed down to him by his father, horn vessels are applied when wet cupping is required. Nowadays glass cups are used for dry cupping. It is prohibited to cut and perform wet cupping over chembe ya mayo.

I asked Sabaya what type of cup was used to cup chembe ya mayo before people had access to glass vessels. He replied, “We used horns before, but a glass cup is used these days because it is easier to achieve the desired strong suction with a flame.”

Levi Ole Lamay applies a cup to chembe ya moyo.

Endnote

- Naturally occurring hollow implements such as horns, gourds and shells were the most likely precursors to more complex cupping technologies, such as those made of bronze by the Greeks during the latter 5th century BC. In 1996, I spoke with a Nigerian man at the Natural History Museum, London, who said in his homeland, people would affix a cupping horn by chewing a certain berry gathered from the jungle, which turned into a gum-like substance. This was pushed into the hole at the top of the horn to stop any air from entering and breaking the seal. Brockbank (1954:68) also wrote that North American natives used a wad of grass tucked away in the cheek, which they would nimbly manipulate with the tongue and manoeuvre into the opening at the tip of the horn.

Bibliography

- Bentley, Bruce (2013) Mending the Fascia with Modern Cupping. The Lantern 10 (3), 4-21. Available online: www. healthtraditions.com.au

- Brockbank, William (1954) Ancient Therapeutic Arts: The Fitzpatrick Lectures Delivered in 1950 and 1951 at the Royal College of Physicians. Butterworth & Heinemann Medical Books. London.

- Fitzpatrick, Mary; Butler, Stuart; and Ham, Anthony (2015) Tanzania. Lonely

Bruce Bentley studied Chinese medicine in Taiwan from 1976 until 1981. He has a Masters Degree in Health Studies based on his thesis entitled Cupping as Therapeutic Technology. He has investigated the Eastern tradition of cupping in Vietnam, and studied at the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Tibetan Medicine Hospital in Lhasa, Tibet, and at the Uighur Traditional Medicine Hospital in Urumqi, Xinjiang Provence, China. To research the Western practice of cupping, Bruce visited the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra where masseurs employ cupping to treat injuries and enhance performance, and in 1998 he went to Europe and North Africa, doing archival research on cupping at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London, and the Department for the History of Medicine at Rome University, followed by field-work in Sicily, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey, Morocco and Tunisia learning local cupping traditions. Bruce’s most recent research trip investigating cupping was in Cambodia during July 2003. He is also a state registered acupuncturist and Chinese herbalist and director of Health Traditions: www.healthtraditions.com.au.

Top ↑