Seven years ago, my brother Grant and his family holidayed on a remote island off the coast of northern mainland Fiji. However, just like it would in any self-respecting horror movie, what began as idyllic turned bad fast. In the morning on day one he was wading at the edge of a lagoon and trod on a stingray hidden under the sand. In defence it responded by driving its venomous tail barb deep into the fleshy inside of his foot. The effect of the deep laceration and toxin immediately brought on intense and unremitting pain. Grant was taken to a small hospital and injected with strong painkillers, but got absolutely no relief. He was told it would be a couple of weeks before he could put any weight on his foot. Somehow, news spread through the village and before long a rap on the window had his wife talking to a young man who asked if Grant might be interested in trying a traditional remedy for stingray trauma. She immediately said yes and soon the boy returned with herbs and a cooker to boil them up. The boy’s mother, the village healer, had instructed him to go to the site of the accident and pick certain herbs growing by the bank. With equipment in tow, he climbed through the hospital window and began boiling the herbs quietly so as not to be found out by the nursing staff. My brother, who remained in unrelenting pain, was instructed to hold his foot above the steam vapours rising from the boiling brew, and was overjoyed in a matter of seconds to discover that his pain almost completely disappeared. He maintained his foot in the steam for about 10 minutes before being asked to immerse it in the herb mix that had since cooled enough to tolerate. Later that evening the treatment was repeated and the next day he was able to walk tentatively. According to Grant it was a timely and unforgettable therapeutic experience. It serves as an irresistible prelude to a series of three essays on steam therapy from Thailand, Vietnam and China.

THE GREEKS AND Romans were ardent admirers of the recuperative power of the steam sauna, and throughout Europe during the Middle Ages, it was a popular place to either lounge about or loosen up and perform gymnastics or receive massage and cupping. As an ongoing sacrament, native North Americans embrace the medicine (sweat) lodge as a bringer of healing and mystical experience; at the hammam, or Turkish bathhouse, sweating followed by vigorous scrubbing and massage combined with stretching and manipulations is a pathway to physical and spiritual cleansing; and in Finland, the ancient institution of the steam sauna includes striking the body with a bundle of silver birch leaves to stimulate the skin, activate the peripheral circulation and detoxify the body. The Finns love their sauna so much that the active three million in operation is equivalent to one for every household. In this distinguished company is the traditional Thai herbal sauna.

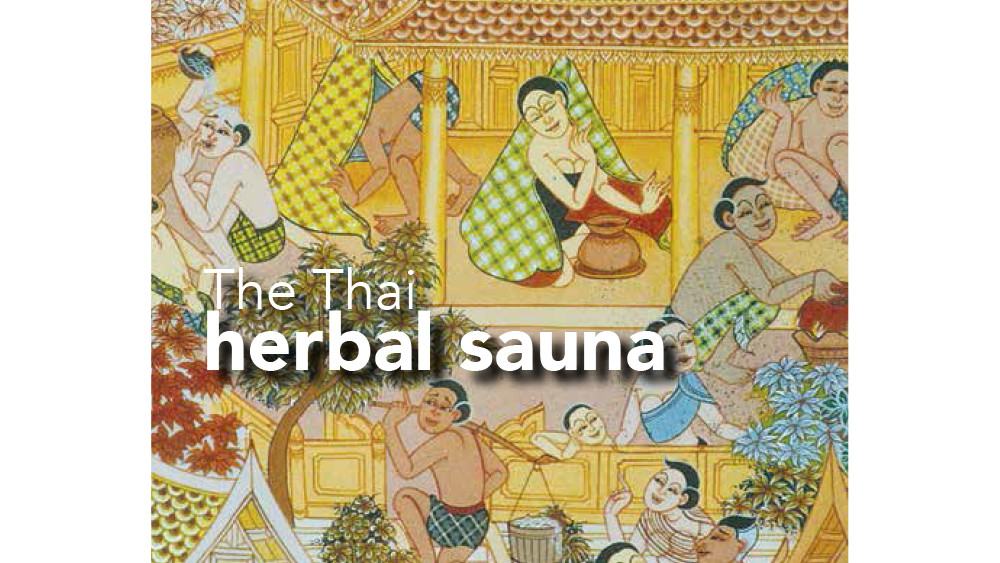

The Thai herbal sauna

One of the naturalistic branches of traditional Thai medicine is the herbal steam sauna (1). Its most rudimentary format simply requires bringing a pot of boiling herbs inside a chamber or sauna room and closing the door, or pulling a plastic flap or a large tropical leaf across the opening to keep in the steam. Another version involves simmering herbs and channeling the steam from an outside cauldron-like closed pot through a pipe into the sauna. After relaxing and absorbing the vapours for 15 to 20 minutes, the same herbal infusion can be poured over the hair and body before drying off.

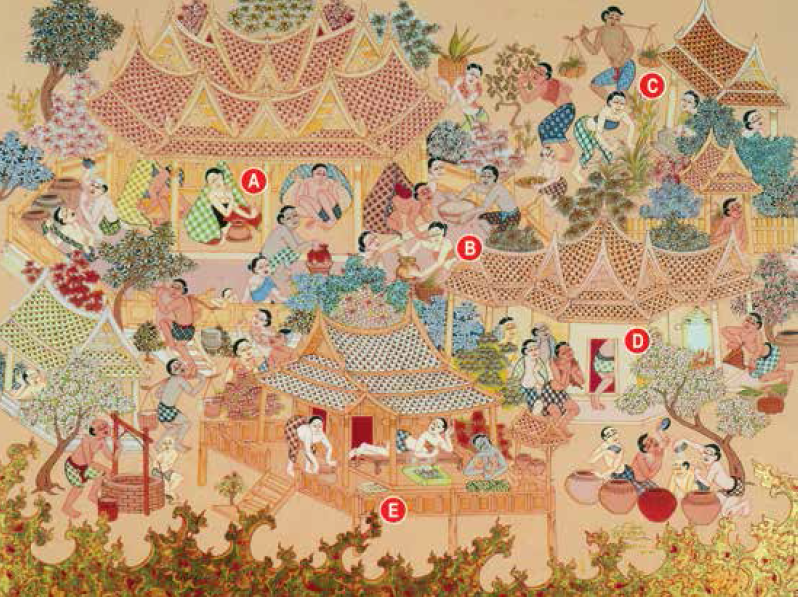

A contemporary artist’s vision of herbal steaming and heat procedures. A. Sauna tents: To the right we see a modified chicken coop sauna. B. Boiling herbs before being taken inside the sauna tent. C. Picking and delivering herbs. D. A group of men entering the sauna room. To the right note a vessel with a steam pipe connected to the sauna wall. E. A woman, whose newborn baby is being cradled, lies on a slatted bed base and absorbs the ascending herb impregnated smoke caused by herbs thrown onto burning charcoal underneath. The herbs are warming and rid coldness due to blood loss and post partum fatigue. Traditionally, a woman receives this treatment for 30 days after giving birth. It is called “dry steaming”, or more literally “staying by the fire”. This practice was rare when I was investigating it a couple of decades back, however I have heard it is making a comeback. In 1996, I saw a slatted bed base with a tray blackened by burning charcoal and herbs used for this purpose in a remote village in rural Nakhon Phanom, a far eastern province. Art by Isara Thayahathai, reproduced from Subchareon (1995).

The benefits of herbs transformed into the subtle medium of steam have five principal rewards. First, certain warming herbs, such as ginger, enhance perspiration and cleanse the body. Second, the therapeutic progress of curative steam begins by opening the pores, which enables the tiny medicated droplets to absorb and make their way into the sen (channels). This in turn clears the jut (points), promotes the flow of lom (the dynamic of wind, closely aligned with the concept of vatta dosha in Ayurvedic medicine), which in turn has the trickle-on effect of balancing the tard (the four elements being earth (paththawithat), air (wayothat), fire (techothat) and water (apothat). The moisture (water) and heat (fire) of the sauna, according to Mr Shan, who I will introduce later, is especially effective for countering dry and cold health concerns. Third, inhaling the steam directly decongests and strengthens the breathing passages and the lungs and dislodges the build-up of sputum and phlegm. Fourth, after the sauna, any additional external herbal ingredients that are best not converted into steam can be applied in the form of a balm or in a poultice and be more effectively absorbed. Fifth, and importantly, the ethereal quality of steam uplifts the spirit and promotes inner peace.

Using biomedically borrowed terminologies, the action of the steam sauna includes the effect of heat to promote perspiration (sudation), dilate the capillaries (vasodilation) and increase peripheral blood flow; leading to an greater oxygenation of the cells, thus hastening the removal of waste and unwanted products (detoxification). A basic further gain, among a host of medicinal others, includes, by virtue of certain herbs such as ginger, camphor and menthol (rubefacients), an increase in skin reddening (erythema and hyperemia), which is caused by the rapid dilation of the capillaries and an increase in local blood circulation. In Thailand in recent times, the herbal sauna has also been employed as part of drug rehabilitation programs and in spas for weight reduction.

Alongside traditional Thai massage

Thai herbal sauna is often followed by traditional Thai massage (Nuad pan boraan or Nuad Thai) (2). Pressing points along the channels not only conveys certain herbs more effectively into the subcutaneous mileu, but also guides others deeper into the interior. In addition, specific herbs that benefit the channels, and their physical materialisations including the fasciae and muscles, have a warming, nourishing and releasing effect, which allows the soft tissue to be more thoroughly relaxed and aligned. The signature Thai style stretches incorporated into a massage routine resemble the health promoting postures developed by the legendary yogi/ascetic known as Phra Rishi. These functional moves are emphasised in the work of many traditional Thai massage therapists (Subcharoen and Deewised, 1995). Therapists (moh nuad) insist that a herbal sauna before a massage initiates a synergistic rapport and adds to the ability to cure of a wide range of internal and external pain and illness syndromes, besides being deeply restorative for the mind and the emotions. When a herbal sauna is unavailable, steamed herbal compresses are also popular and effective (see instructions on Page 22). A compress can be pressed and rubbed into the body, either as a treatment in itself or during a traditional Thai massage.

A therapist at an Ayurvedic Hospital in Jaipur, India, holds a nozzle attached to a tube from a boiling pot of herbs selected for their antiinflammatory effects, and sprays medicated steam on the shoulder of a patient suffering rheumatoid arthritis. (Photo taken by Bruce in 1990.)

Historical speculations

It is possible that the Thai herbal sauna is an indigenous creation. If however it were inspired by an outside influence, then the most likely source would be India; since from early on in first millennium AD, many facets of Indian culture, including medical practices, have been welcomed into the fabric of Thai society. It is written in an ancient Indian medical text that, “when sweat comes there is general relief for problems where the person is entered by wind” (Basham, 1976:22). Also in early books on Buddhist treatments for “Wind in the Limbs” and “Wind in all Parts”, it is recommended to treat by “sweating by the use of provisions” (Zysk, 1991:93). Another treatment describes steaming “by the use of different kinds of leaves and sprouts”, whereby, “the afflicted person should enter a ‘water storeroom’ (udakosha) half filled with ‘wind destroying drugs’ that should cause him who is to be sweated, after he has entered a cauldron (kataha) half filled with water warmed and purified” (Zysk, 1991:95). Nowadays, a widespread practice in the Ayurveda is swedana, or the herbalised steam bath treatment.

If there were early Thai written records of the herbal sauna then sadly these appear to have vanished, along with countless other books, records and medical manuscripts. One major reason for this is because the Thais and the Burmese have been at each other’s throats, tit for tat, for centuries. In 1767, the Burmese thoroughly ransacked the libraries and annihilated the then capital, Ayutthaya. In response, the King moved the royal court and established Bangkok as the new capital. One of his first decrees was to build the Wat Pho temple, and have craftsmen carve some of the medical knowledge, herbal formulas and charts showing the course-ways of the channels and the location of points on stone tablets, so they would be less easily destroyed. These are on display in one of the pavilions in the grounds at Wat Pho, the largest Buddhist monastery complex in Thailand.

The Royal and folk medical traditions

The Thai herbal sauna, like internal herbal medicine and massage, has two streams. One is called “the Royal tradition”, and is literate scholarly and theoretically based on classical Ayurveda. The other is grounded in local (often rural) knowhow arrived at by trial and error. The transmission of folkloric practices of this kind is rarely by writing and their survival relies on oral communication and instruction from generation to generation. In this essay, it is mostly from this folk tradition that the information is gleaned, including some of the effects of the herbs. In lieu, there is ample cause to believe that rural herbal saunas have existed for a long time indeed, far longer than living memory, since practitioners throughout the different regions of the country use a range of herbal formulas that depend almost exclusively on the plants available from nearby locales. Such intimate empirical knowledge is unlikely to have come about in a relatively short period of time.

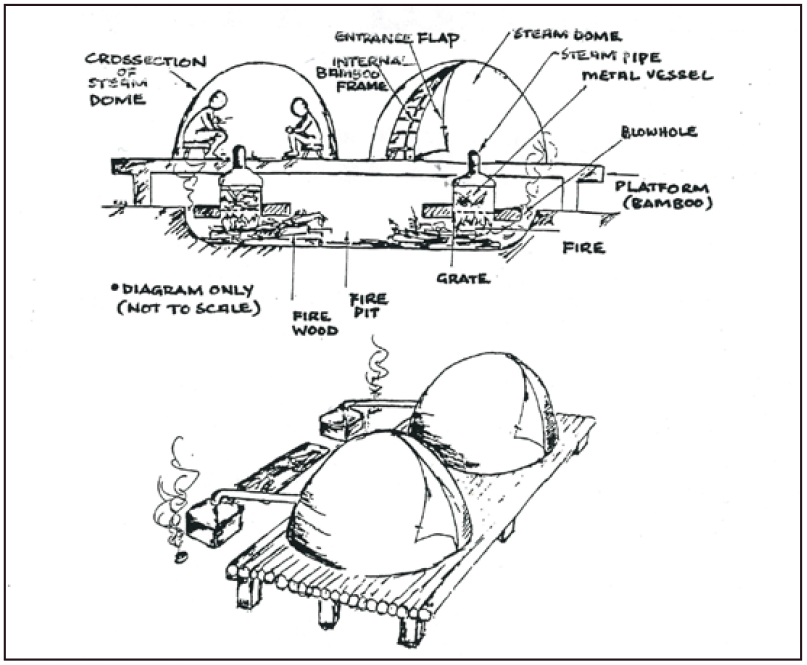

Design, construction and operation

Although there are modified Western-style herbal sauna systems in the cities, resorts and spas, the ones in villages and small towns are unique and intriguingly Thai. During my first trip to Thailand in 1976, I was trekking alone for two weeks in rugged far northern Chiangmai province and staying overnight in villages. There I experienced the herbal sauna for the first time. It was a chicken coop made from woven bamboo strips covered with big jungle leaves with a small stool to sit on inside. The base of the coop needed to be lifted to wriggle in. Then a pot of boiling herbs was passed underneath. After a strenuous day, it was a godsend.

In 1989, I discovered another herbal sauna, as well as two notable informants: Mr Doi and Mr Shan. Mr Doi was the proprietor of a small guesthouse (and herbal sauna) in Sangkhom, in northern Isaan (Nong Khai province). His delightful accommodations, comprising half a dozen thatched bamboo cottages overlooking the Mekong River, with the green backdrop of Laos in the distance, were a well-earned stay for the trickle of travellers who passed by this off-the-touristmap neck of the woods. Like many terrific field research occurrences, how I ended up there happened by chance. After six weeks of intense investigations into shamanic and supernaturalistic curing, which included two weeks in the Chinese majority city of Penang in northern Malaysia, I needed some time out, and decided to slowly bus around the eastern border, before ending up just north of Chiangmai city to attend the annual northern Thailand shaman’s party. Along the way I liked the look of Sangkhom and jumped off. “Time out” however didn’t last long after I met and befriended a great man in his mid-70s named Mr Shan. As a lad he had been a monk at Wat Pho temple, which forever will be the scholarly heart of the Thai “Royal” herbal and massage tradition. I had previously studied there a couple of times myself and had fond memories.

Mr Shan, who had since become a regular householder, had remained a massage therapist by trade, and worked part-time at the guesthouse. He carried on practising the deep and slow variation of massage taught to him at the temple in the 1920s and ’30s. Receiving instruction from him seemed all the more vital and significant since no one is his family, or anyone else for that matter, had been interested in learning it from him, and this distinct style, to the best of my knowledge, was no longer being practised at Wat Pho or elsewhere.

Mr Shan sometimes also gave counsel to Mr Doi regarding which herbs to use in his sauna. The set-up was another chicken coop (there are many in Thailand), but this time it was covered with plastic sheeting— modernity had struck! Mr Doi had a pot of boiling herbs outside the sauna, with a pipe from the top transferring the steam into the interior of the sauna coop. Like many other places where a herbal sauna was operating, lots of the herbs that he regularly used, such as lemongrass, galangal, and kaffir lime, were being cultivated in his backyard garden.

Here is Mr Doi and Mr Shan’s basic prescription for the herbal sauna:

- Ginger – 3 cups

- Cassumunar Ginger – 4 cups

- Kaffir lime – 4 leaves

- Eulalyptus leaves – a generous handful

- Camphor – half teaspoon

- Menthol – half teaspoon

- Lemon grass – 3 whole stalks

- Flowers – any white flowers – but jasmine and lotus are the most desirable (and auspicious). To enhance the wonderful aroma of this recipe, cinnamon leaf may also be added.

Jan Singkan’s herbal sauna system stands in a yard full of herbs, fruit trees and a couple of loofa vines. (Illustration by my father, Keith Bentley, in 1992.)

Another time, in 1992, I studied a form of Burmese massage (3) with Mr Jan Singkan in Pai, a village in North Western Thailand (Mae Hong Son province). Jan had a deep knowledge of the forest, and at first light each morning we would go looking for the herbs he needed to use in his saunas to treat his patients of the day. Their problems were as diverse as aching cold legs, back injury, abdominal bloating, migraine and so forth. Each formula consisted of six to 10 herbs. He was taught Burmese massage and herbal knowledge for the sauna by his father and grandfather, and in keeping with tradition he was training his two young daughters.

“Pressing points along the channels not only conveys certain herbs more effectively into the subcutaneous mileu, but also guides others deeper into the interior.”

Compared to what has been surveyed so far, Jan’s sauna set up was decidedly glamorous, and although the action took effect inside yet another chicken coop, it was above ground and larger than regular models. A dug trench acted as a fire pit, with wood fed in to boil the herbal contents contained in two square tin pots that were suspended and held in place by the hardened clay-based soil. The rising steam from the boiling brew was then funneled through a pipe inserted into each sauna, which could comfortably accommodate six adults seated facing each other on two wooden benches.

A prospective basic nomenclature for commonly used sauna herbs

Many herbs that are used in sauna treatments may be classified into five types:

- (1) Aromatic herbs such as jasmine, lotus, turmeric, camphor, eucalyptus leaf, lemongrass, kaffir lime and ylang ylang contain volatile oils as principal active components. Aromatic herbs are often calmative and diffuse into the heart. They have the following merits:

- Possess a sublime aroma

- Relax emotions and lift the spirit

- Stimulate peripheral circulation

- Soothe skin conditions

- Relieve nasal and respiratory conditions.

- (2) Herbs with a sour taste. In Thai Royal herbal medicine, herbs are formally classified according to their taste. Many of the herbs used in the herbal sauna, such as kaffir lime, lemongrass and tamarind, are in a group of sour (mildly acidic) herbs that have mild antibacterial and cleansing properties. They are effective for relieving chest congestion and strengthening respiratory function, as well as healing many skin diseases.

- (3) Herbs with a hot taste (and nature) dispatch heat to allow other herbs to penetrate into deeper levels of the body. Hot herbs include cassumunar ginger, ginger, turmeric and eucalyptus.

- (4) Herbs with a calmative nature such as jasmine flowers and menthol neutralise febrile illnesses, inflammations and open wounds, calm aggravated emotions and bring a sense of peace.

- (5) Local additions. Herbs indigenous to the local area of every informed herbal sauna exponent are often added. These include phak naam (Lasia spinosa, stem) for measles and fever accompanied by rash, soap berry fruit (prar karm dee khwai, Sapindus emarginatus) for seborrhoea and fungal infections, castor oil plant leaves for infected wounds and chingchee (Capparis micracantha, stem and leaf) for bronchitis and infected skin diseases. Many indigenous rural herbs have no formal classifications and are used purely because they have been found to be effective.

Fresh herbs

Fresh herbs are always favoured for their natural constituents, most notably their volatile oil components that are reduced or lost during the drying process. Rural practitioners gather the majority of their herbs from either their garden, or from local fields, forests, jungles, mountains, ditches and riverbanks. Some herbs however may also be brought in from afar. Mr Doi said that he buys some of the herbs he uses for his herbal sauna from Lao traders who cross the river by canoe into his locale. When I was there, he was using the crystalline form of camphor, instead of from natural plant gum, because he said that recent heavy monsoons had caused the forest sources to rot.

Contraindications and cautions

Do not enter the herbal sauna if the following applies: during pregnancy, fever, hypo or hypertension or heart disease. The herbal sauna is also not recommended for hot body conditions or for those with fiery temperaments (excess fire element). Allow the body to dry off in the sun or rubbed dry with a towel after a few minutes, and sit and relax for a while. Be sure to drink plenty of water (but not chilled) afterwards.

Herbal sauna pharmacopoeia

The following is a list and description of some of the key ingredients in the herbal sauna. They are traditionally combined to assist in alleviating ailments such as respiratory complaints, certain skin diseases, emotional distress, insomnia, aching muscles, soft tissue injuries and common colds. Many of these herbs also happen to be essential ingredients in Thai cooking, and are readily available in Oriental grocery shops in Western countries. Some of the herbs, such as the rhizomes, can be either pounded or sliced into small portions, while some leaves including kaffir lime, eucalyptus and tamarind are best bruised in a mortar and pestle to release their aromatic oils before being added at the very end stage of preparatory boiling. When fresh ingredients are unavailable or too costly, some may be included as an essential oil such as ylang ylang (magrut).

Jasmine (Mali, Jasminum sambac) Sauna applications: The flowers are picked in the evening before they open. They are highly valued in the herbal sauna because they have a sublime and uplifting fragrance and their white colour and aroma represent purity. Jasmine is often an integral part of Buddhist ceremonies. The flowers are considered calmative and used for anxiety, stress headache and insomnia. A drop or two of jasmine essential oil can be used if the flowers are unavailable. Characteristics: Cool and aromatic Part used: Flower

Lemongrass (Ta krai, Cymbopogon citratus) Sauna applications: Cleanses and deodorises the skin, benefits the eyes and clears stuffiness in the head. Acts as a calmative, restores the spirit and alerts the senses. Extensively used for colds, chest congestion, asthma, fever, cough, sore throat, laryngitis and headache. Among the Hmong hill tribes of Northern Thailand (4), lemongrass is steamed as a general tonic by stimulating blood circulation and for treating bone and joint pain, sprains, bruises, and sore muscles. Mr Jan also used it for abdominal pain, distension and nausea. A combination of skin enhancing herbs, including fresh lemongrass, has a remarkably effective smoothing effect. Is also used to cure hangover. Lemongrass has rubefacient effects and is also an important addition to the Thai herbal compress. Characteristics: Hot and aromatic Parts used: Leaves and stem

“Fresh herbs are always favoured for their natural constituents, most notably their volatile oil components that are reduced or lost during the drying process.”

Lotus (Bua luang) Sauna applications: The beautiful white lotus flower is honoured for bestowing purity. It has the benefit of calming the nerves. Characteristic: Neutral Part used: Flower.

Ginger (Khing, Zingiber officinale) Sauna applications: Often used to induce perspiration. Ginger has a stimulating and warming effect, relieves wind and cold conditions including abdominal discomfort, nausea and painful and irregular menstruation, and balances the four elements. Also used to treat contusions, general body aches and discomfort, as well to improve circulation. Has a powerful effect especially at the beginning of the common cold. As a skin herb, it relieves fungal conditions, infections, pimples and acne. Characteristics: Hot and aromatic Part used: Rhizome.

Tumeric (Khamin chan, Curcuma longa) Sauna applications: Reduces inflammation and is effective for insect bites, wound healing and skin diseases (being astringent and antibacterial). Strengthens the digestion and so eases indigestion and gastro-intestinal complaints. An important addition to the Thai herbal compress. Characteristic: Hot Part used: Rhizome, leaf.

Galangal (Khaa, Alpinia Galanga) Sauna applications: Promotes circulation, speeds healing of contusions and treats skin diseases. An essential herb to treat early stage common cold. Used both in herbal saunas and in herbal compresses for moving blood, healing bruises, curing skin diseases including acne, and for flushing out toxins. Mr Doi said it was an excellent sauna herb to stimulate the digestion and rectify bloating, nausea and diarrhoea. Characteristics: Hot and aromatic Part used: Rhizome.

Cassumunar Ginger (Plai, Zingiber Cassumunar) Sauna applications: This rhizome relieves tight, stiff muscles, assists wound healing and benefits menstrual discomfort, joint sprains, inflammation and skin diseases as well as being an effective insect repellent. Like common ginger, it is also used as an antiseptic for wounds, cuts, and skin infections. After childbirth, women traditionally drink cassumunar ginger tea for one month to move wind from the abdomen. An important herb in the Thai herbal compress to relieve pain and reduce swelling. Used postpartum for dry steaming. Characteristics: Hot and aromatic Part used: Rhizome.

Kaffir Lime (Ma krut, Citrus hystix) Sauna applications: Penetrates to alleviate headache and dizziness. Inhaled to treat colds, congestion, and cough. Taken internally, it stimulates the digestion to alleviate flatulence and indigestion. It is used to promote regularity in the case of blocked or infrequent menstruation. It is well known as a blood purifier, as an antioxidant with cancer-preventing properties, and is used to treat high blood pressure. When fresh leaves are unavailable, they can be bought and kept active by freezing in an airtight bag. Mr Shan adds the peel to the sauna as a heart and digestive tonic. A principal herb in the herbal compress. If unavailable it can be swapped for regular lime. Characteristics: Sour, warm, aromatic and refreshing. Part used: Leaf, skin/peel.

Eucalyptus (In yu kha, Eucalyptus globulus) (5) Sauna applications: Often used in herbal steams to relieve respiratory conditions by opening the breathing passages, clears the sinuses, decongests the lungs and relieves cough (anti-viral), and for sprains, bruises, and sore muscles (anti-spasmodic effects). Characteristics: Hot and aromatic Part used: leaves.

Camphor (Ga ra boon, Cinnamonum camphora) Sauna applications: A strong decongestant, it is inhaled to treat colds, clear blocked sinuses and relieves congestion, sore throat, cough, sinusitis, and bronchitis by opening the breathing passages. Use the crystals sparingly as they can be overpowering. Mr Shan and Mr Doi spoke of camphor being beneficial for menstrual irregularity and its effectiveness in treating fevers, arthritis, softtissue injuries, pain, and cuts and lacerations, as well as being soothing for bites and stings. Characteristics: Hot taste, cooling and antiinflammatory, aromatic and refreshing Parts used: Gum of tree trunk or in crystalised form, or the leaves. Crystals are distilled from the gum or resin of a type of cinnamon tree.

Menthol crystals (Pimsen, Mentha crystals, Hexahtdrothymol-1) Sauna applications: With a fragrance similar to camphor, it is often used in herbal saunas and inhalations. It is effective for common cold and flu symptoms, including nasal stuffiness and congestive coughs. Also used for muscle aches and sprains. Characteristics: Cooling, aromatic, refreshing Parts used: Crystals are made synthetically or derived from a variety of mint plants.

Tamarind (Ma Khaam, Tamaridus indica) Sauna applications: Calming, wound healing, treats skin lesions, eczema, boils, ulcers, sores and infected wounds (antiseptic qualities), relieves pain and swelling and arthritis. Used also as a general tonic and helps other herbs penetrate into the body. Characteristics: Cooling, aromatic and refreshing Parts used: Leaves.

Pandanus (Toei, Pandanas tectorius) Sauna applications: The long narrow leaves have a wonderful fragrance which imparts a calmative effect. Used as a tonic for the heart, the blood and the digestive system. Characteristic: Sweet, cooling Part used: Leaf.

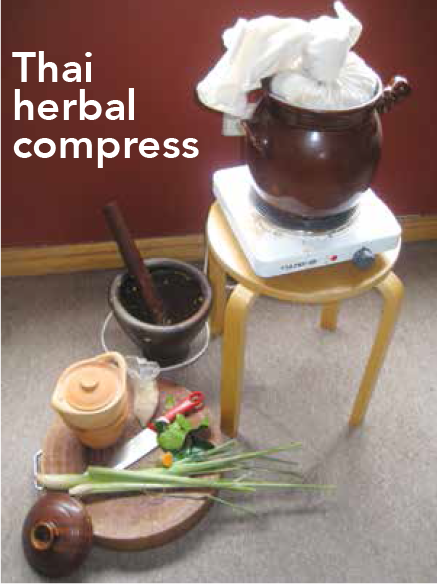

The steamed herbal compress (luk prakob) is popular in Thailand and is offered throughout the country, from storefront massage establishments to high-end spas, to the traditional Thai massage pavilion at Wat Pho temple.

How to make the herbal compress

- Gather the appropriate fresh herbs.

- Pound the rhizomes and coarse herbs and shred or bruise any leaves.

- Lay the herbs on square piece of muslin cloth.

- Draw the four corners and tie the cloth into a bundle (use string or a rubber band).

- Steam the herbs over hot water until thoroughly heated (15–20 minutes).

- Turn the heat down and leave herbs until required.

- Before practice, some therapists dip the hot herbal compress into Thai whiskey to assist the various herbal actives better absorb.

- Test patch the skin first! Be careful not to burn the skin if the bundle is too hot. If too hot it may be wrapped in another layer of muslin.

Practice: Apply the herbal bundle with a press and roll action all over the body. Skilled practitioners use one hand to work the compress while the other kneads and massages the herb-infused flesh. As well as smelling sublime, the hot compress alleviates pain and inflammation, deodorises and cleanses the skin, and is especially good after physical exertion and post partum. It is often used when a herbal sauna is unavailable.

Recipes: The basic recipe from The Old Medicine Hospital in Chiangmai comprises ginger, mint leaves, lime fruit, lemongrass and eucalyptus.

Another formula, this time from the Thai herbal massage teacher Pikul Thermyote is made up of the following:

- 2 cups of pounded Cassumunar ginger

- 1 whole kaffir lime, chopped

- 7 eucalyptus leaves ½ to ¾ teaspoon camphor crystals

- 1 node of pounded galangal and turmeric.

Endnotes

- (1) Tu op samunphrai is the Thai term for a small sauna able to accommodate one person, while hong op samunphrai is a larger herbal sauna able to seat two or more people. Samunphrai means “herbal medicine”.

- (2) In some establishments, the herbal sauna follows traditional Thai massage, however in my opinion, and according to Mr Jan, Mr Shan and Mr Doi, the best results are achieved before, for the reasons given in the text.

- (3) This style of Burmese massage was created in the Shan state, a large region of northeastern Burma. It is a full body one-hour routine divided into two sections. Part one consists of circular double palm pressing movements throughout the entire body surface, followed by part two, which comprises mostly stretching manoeuvres.

- (4) The Hmong, one of the hill tribes living in the forests of far northern Thailand, are renowned for their herbal and environmental wisdom. Other hill tribes call them “the keepers of the forest”. It was a joy discovering even a little of what they were kind enough to share.

- (5) The eucalyptus tree is an import that is controversial in Thailand. Sadly the benefits of the fresh leaves are a high price to pay for the anger and resentment many villagers and ecologists in particular feel about this Australian species. The excellent book Behind the Smile (Ekachai, 1990) is a collection of essays on the social and environmental issues that are altering and fragmenting traditional lifestyles in rural Thailand. In many of these stories, the locals voice their protest against government backed commercial eucalyptus projects. “It is ridiculous,” says a village leader, “Why cut down trees to plant trees? Why destroy an important source of food and medicine? City people never understand how much the forest means to us. We have friends and relatives in that area,” says Poh Onn, “and they have warned us about this dangerous tree. It hardens the land, consumes too much water and its roots kill other trees and plants nearby.” Of course the benefits of fresh eucalyptus leaves for the herbal sauna has absolutely no bearing on why the government or businessmen cultivate the tree. Therapists understandably utilise the leaves because the tree is there. Overall it is an unsatisfactory presence, considering the far-reaching negative impact the tree has on natural Thai eco-systems. Eucalyptus oil can be easily substituted for fresh leaves, just as other ingredients such as camphor can be added in crystalline form instead of cuttings from the plant.

Bibliography

- Ekachai, Sanitsuda (1990) Behind the Smile: Voices of Thailand. Post Publishing. Bangkok.

- Basham, A. L. (1976) The Practice of Medicine in Ancient and Medieval India. In Asian Medical Systems: A Comparative Study, edited by Charles Leslie, University of California Press. Berkeley.

- Subchareon, Pennapa (1995) The History and Development of Thai Traditional Medicine. National Institute of Thai traditional Medicine, Department of Medical Service, Ministery of Public Health. Bangkok.

- Subchareon, Pennapa and Deewised, Kunchana (1995) The Hermit’s Art of Contorting: Thai Traditional Medicine. The National Institute of Thai Traditional Medicine. Nontaburi, Thailand.

- Zysk, Kenneth G. (1991) Asceticism and healing in ancient India: medicine in the Buddhist monastery. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

My heartfelt thanks to all the other people in Thailand who shared their knowledge. They include Mr Muni, a farmer in Chiangmai province, my teachers at Wat Pho, most notably Ms Pian and Ms Kannika, the late Dr Pennepa Subcharoen, former Deputy DirectorGeneral, Department for Development of Thai Traditional and Alterative Medicine, Ministry of Public-Health, for showing and explaining the sauna herbs growing in her extensive herb garden, the late Mr Siripron, former President of the Thai Traditional Medical Association, and Mr Preeda Tangtrongchitr, Director of the Wat Pho Massage School, for his encouragement and camaraderie.

Bruce has been to Thailand 13 times, adding up to around two and a half years of research into Thai traditional medicine. He is the director of the Australian School of Traditional Thai Massage and a registered acupuncturist and Chinese herbalist who also teaches cupping and gua sha workshops. Visit: healthtraditions.com.au. Facebook: facebook.com/ HealthTraditions.

Top ↑