Explorations of Cupping in Greece

Published in The Lantern

Bruce Bently

Melbourne, Australia

By Bruce Bently

Despite encroaching modernity, cupping in Greece continues to be a popular healing method, passed down through generations as a family tradition.

Dr Manzanas began by telling me about his mother cupping everyone in his family using ordinary coffee cups. He then recalled that during his medical student years at Athens University, from 1952 until 1959, cupping, although not taught, was discussed by some of his lecturers who “had a good opinion of it, especially for common cold, pneumonia, bronchitis and pleurisy”. The older professors even strongly recommended it, in contrast to his medical books that stressed that antibiotics were far more effective and scientific than any other mode of treatment. Dr Manzanas believed that cupping was not instructed because the lecturers realised that most of the students had already been shown how to perform it by family members at home. He said that even today, “in every household throughout this rural region, at least one family member can perform it”, so consequently he finds no need to use cupping in his own practice, although he does often advise patients to “go home and get your mother to do the cupping.”

Dr Manzanas went on to say (what other Greek nationals in Greece and in Australia have also confirmed), that the Greeks use cupping mostly to treat respiratory conditions. He said, “Greek people recognise the major benefit of cupping is to cure the lungs, by decongesting phlegm from the lung tissue and take out the coldness.” Dr Manzanas cautioned however, “It is only beneficial in treating common cold so long as the patient stays at home in the warm for at least 12 hours after treatment. Otherwise, to go outside when the skin pores are open will make the condition worse.”

Whenever I hear this requisite I get reminded how well cupping lends itself to being a home-based folk treatment, whereby the patient has no need to go elsewhere and can stay warm, cosy and protected indoors. As in China, the Greeks are very particular about protecting the local skin surface during and after cupping. This means that irrespective of how much a patient can benefit from cupping, if they expose themselves to adverse weather conditions after treatment, it is better that they had never been treated in the first place.

It is intriguing to ponder how and when cupping became a commonplace lay Greek practice with an emphasis on treating respiratory ailments. According to the eminent classical scholar W.H.S. Jones (1959, p. xii), in Greece around 400 BCE, “the most important diseases of the Hippocratic age were the chest complaints, pneumonia and pleurisy (pulmonary tuberculosis was also very general) and various forms, subcontinuous and remittent, of malaria.” Yet somewhat surprisingly, within the 60-odd volumes of the Hippocratic Corpus, there is not a single recommendation made for cupping as a treatment for pulmonary conditions – although it does get advised for conditions such as staunching excessive menstrual bleeding and correcting certain spinal misplacements.

By contrast, in the present era of Greek folk medical practice at least, treating common cold and other respiratory conditions is almost the staple for cupping – in much the same way as it is employed in other households elsewhere throughout parts of traditional Europe.

We can only presume it has been practised by householders for centuries, yet for precisely how long is impossible to gauge because of a lack of written record. Oral histories can certainly take us back a few generations, but beyond that things get hazy. In Greek practice, cups are often applied to the skin surface for only a short period of time – a few seconds – then removed and reapplied elsewhere in a progressive sequence.

Apparently, the initial few seconds of a cup being placed on the skin surface are the most effective in withdrawing climatic pathogens. In many practices I have even observed the cups being “slapped” onto the body with a loose flick of the wrist to dramatically impact on the flesh and powerfully draw coldness and dislodge congestive conditions such as mucus from the lungs.

According to Dr Manzanas, the most important etiological factor causing respiratory disease is climatic or environmental cold entering inside, either by the breath (via inhalation) or, even more significantly, through the pores of the skin, particularly at the back of the neck and throughout the thoracic region.

In his opinion, people in Greece think mostly about coldness being the fundamental reason for such illnesses, because as a subjective feeling “it feels more obvious than the others”. He added that when associated with wind, cold was deemed even more pernicious, because the wind unsettled the protective skin layer and drove the cold even further into the body. Ultimately, Dr Manzanas said the most invasive and damaging combination of weather factors occurred “when cold, moisture and windy weather all combine together”. After 40 years of clinical practice, he is convinced that “cupping takes these out from the body better than any other treatment”. As a result “we can say, therefore, that traditional folk etiologies for respiratory diseases and other conditions that respond to cupping are good and true explanations.”

Dr Manzanas also talked about other reasons for applying cups. He recommended them as a treatment for all kinds of pain in the stomach, including dyspepsia, vomiting, nausea and pain due to coldness. His treatment advice, other than cupping directly and extensively throughout the upper back for pulmonary problems, also included placing a cup over the navel for half an hour or longer to “take out the store of cold” from the body in such cases of “weakened immunity”.

He also recommended cupping for stiffness throughout the lower back, as well as on the legs to improve blood circulation.

The close association between these indigenous Greek medical ideas and those held within traditional Chinese medicine is indisputable. At one point I enquired whether he was at all familiar with traditional Chinese medicine, and he answered, “No.”

Finally, I asked Dr Manzanas if he knew any young doctors who held positive views about cupping. He lamented: “Unfortunately not. I believe it has to do with big business, pharmacies making money, and not being impressed about people being able to treat themselves.” Incidentally, Dr Manzanos was the only person I met in Greece who referred to cupping as sikia, the original Greek word used by the Hippocratic physicians, instead of the Latin based term vendouzes, which seeped into the popular vernacular and stayed on from Roman times. When I commented on this, he smiled and said he preferred the original.

“Irrespective of how much a patient can benefit from cupping, if they expose themselves to adverse weather conditions after treatment, it is better that they had never been treated in the first place.”

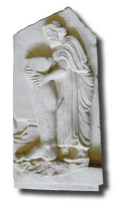

When it was time to part, Dr Manzanas presented me with a gift of a votive replica from an 8th century BCE healing sanctuary dedicated to Asclepios, the God of Medicine and Healing. Depicted is a venerable bearded man in classical robes, holding an enlarged leg (pictured left).

Detail on the medial aspect of the lower leg shows an enlarged great saphenous vein (from the Greek safaina meaning “to be clearly seen”), which may indicate that the person who commissioned this relief and offered it to the god was suffering from a varicose problem. It has hung in my office ever since.

Cupping is a wonderful field research subject, because one can be quickly whisked away from the regular tourist tracts and into homes and conversations deeply in tune with the local culture. It has been a privilege to meet such honest, earthy people. From my journal, I will now recount the three days I spent in Ioannina (pronounced yah-nih-nah), a picturesque city beside a large lake (Lake Pamvotis) some 100 km from the north-eastern coastline.

On day one, I spoke with the very helpful Vicky Kalfakakou and Angelo Evangelou, Associate Professors at the University of Ioannina’s Laboratory of Experimental Physiology. Vicky’s mother had been a nurse all her working life and also “had lots of cupping experience” – so she was eager for me to meet her. When we met that evening, her mother told me, “the main purpose of cupping is to create warmth and hyperemia in order to draw coldness from the body – not only from the surface tissue but also from deeper levels.”

Mrs Kalfakakou also suggested I talk with the local fishermen. So the next morning I walked down to the pier, where I asked a man who owned a small boat if he could take me to the nearby island. There I chanced to meet a seasoned fisherman, Janus Sadas, who said: “I always get cupping if I feel unwell. But these days most people I know take the easy way and get injections or take pills. No good for the body. You know, 40 years ago everyone did it, but things have changed a lot. Before, especially for fishermen, when they go to get the fish, it is often cold, rain and wind, sometimes snow, and they would get cold and pneumonia. They often had the vendouzes done.”

Later that same day, I didn’t have to go far to meet another very supportive person interested in cupping. At the small hotel where I was staying, the landlady Soula Tzabana’s eyes lit up when I told her about my work. Soula had inherited her cupping skills from her 99-year-old grandmother. She was so enthusiastic that even before our interview began, she declared, “I’m very interested … I love it!” Soula told me she became a cupping fan after her grandmother quickly cured her of an illness. She kindly gave me instructions on her family cupping practice, together with a practical demonstration, which she performed on another person working at the hotel.

Soula Tzabana’s cupping treatment

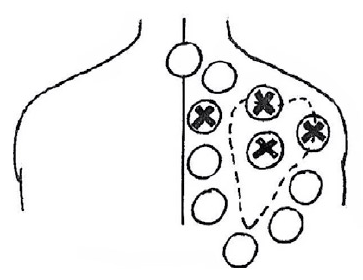

Soula’s practice, delineated by stages, highlights what a positive indicator cupping marks are in establishing the presence of pathogenic coldness. Stage 1 determines where it is lodged within the body, by the show of a dark circular mark or series of marks, during and after the quick application of cups. Stage 2 concentrates on drawing this cold from deeper levels within the body, by leaving cups on focal sites for a longer period of time. This treatment remedies common cold, influenza, bronchitis and muscular aches.

Treatment procedure

In Stage 1, the practitioner stands beside the table applying, then taking off, cups and reapplying them in a constant stream of activity. The tempo is brisk. There is a slapping sound as each cup lands on the skin. The intention is to have the cup strike and intensely concentrate the release of contracted cold and wind factors lodged within the outer layers of the body. Use five or six heated cups warmed to at least body temperature. With practice you might even get as good as Soula’s grandma – “my grandmother used only two glasses; her skill was very good.” This indicates she was very swift and dexterous. The practice sequence is as follows:

Stage 1

- Start on the right side of the body and place the first cup on one of the locations where “X marks the spot”.

- Apply the remaining four or five cups in a counter-clockwise direction around the perimeter of the scapula, including one, at random, in the centre of the scapula above the infraspinatus muscle (the location of Tianzhong SI-11).

- Having fixed these five or six cups, immediately remove the first cup and transfer it to the next position, until the circumnavigation around the scapula has been completed.

- In the same manner, the next cup is placed lateral to T1, followed by another directly above the space between C7 and T1 (Dazui Du 14). According to Soula, both these locations are “important points to treat cold”, especially when hot symptoms coexist.

- Do the same to the left side of the upper back by repeating Steps 1 – 4 (working clockwise).

- Repeat the above steps five to 10 times.

Stage 2

- Note those marks that have become dark and cup them again. Leave the cup(s) in situ for three minutes. Cover the entire back with a towel or thick blanket.

- Remove all the cups and massage the back to warm and invigorate the circulation. In Greece, alcohol is often rubbed into the skin after cupping in order to warm and close the skin pores, so they are less vulnerable to another bout of external climatic attack.

Soula is passionate about cupping. She said more than once, “Cupping will always continue because it is effective. Young people must know about this. We must pass it on.”

Margaret Moukas’s method for ridding the upper back of cold

On day three in Ioannina, I went into a shop looking for a snack and during pleasantries asked the woman serving if she knew anyone I could talk to about cupping. She said, “Sure, my mother” and invited me for dinner to meet her that evening. Christine, the shop owner, translated for her mother Margaret Moukas, who was about 70 years old. She said, “This is our family method from my grandmother. Our family cupping method is a quick answer for cold and pain.”

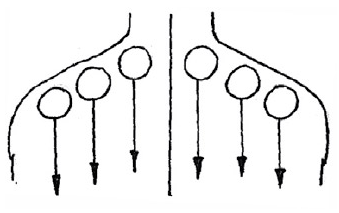

Margaret’s method is to apply, without any lubrication to the skin, six quick parallel downward swiping movements using the same cup (see sketch).

Margaret Moukas’ method for ridding cold in the upper back

At the moment of contact, she draws the cup downwards for about 6–8 inches (15- 20 cm) until it “naturally” leaves the skin.

Margaret said to avoid the spine in this treatment. I was told, “Not down the backbone, the cups need meat!” I was also informed that with each downward sweep of the cup “the body tells you how far each cup should travel, because the cold that it draws out acts as a gauge and naturally releases the grip of the cup from the skin surface when it has done what it needs to do”.

“We can say, therefore, that traditional folk etiologies for respiratory diseases and other conditions that respond to cupping are good and true explanations.”

Margaret recommended each line be swiped only once. “It’s not necessary to do any more.” This method, while robust, is very satisfying to receive and feels like a cross between a cupping and a gua sha treatment.

Bibliography

- Jones, W.H.S. (1959) Hippocrates. Volume II. Great Britain: William Heinemann.

This essay is based on two weeks spent in Greece during May 1998. Bruce is looking forward to visiting Greece again for six weeks during March and April 2013, for more cupping explorations. A version of this essay was first published online at www.junkyardaoist.com in 2011. Many thanks to Michael Max for sharing.

Bruce Bentley studied Chinese medicine in Taiwan from 1976 until 1981. He has a Masters Degree in Health Studies based on his thesis entitled Cupping as Therapeutic Technology. He has investigated the Eastern tradition of cupping in Vietnam, and studied at the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Tibetan Medicine Hospital in Lhasa, Tibet, and at the Uighur Traditional Medicine Hospital in Urumqi, Xinjiang Provence, China.

To research the Western practice of cupping, Bruce visited the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra where masseurs employ cupping to treat injuries and enhance performance, and in 1998 he went to Europe and North Africa, doing archival research on cupping at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London, and the Department for the History of Medicine at Rome University, followed by field-work in Sicily, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey, Morocco and Tunisia learning local cupping traditions.

Bruce’s most recent research trip investigating cupping was in Cambodia during July 2003. He is also a state registered acupuncturist and Chinese herbalist and director of Health Traditions: www.healthtraditions.com.au.